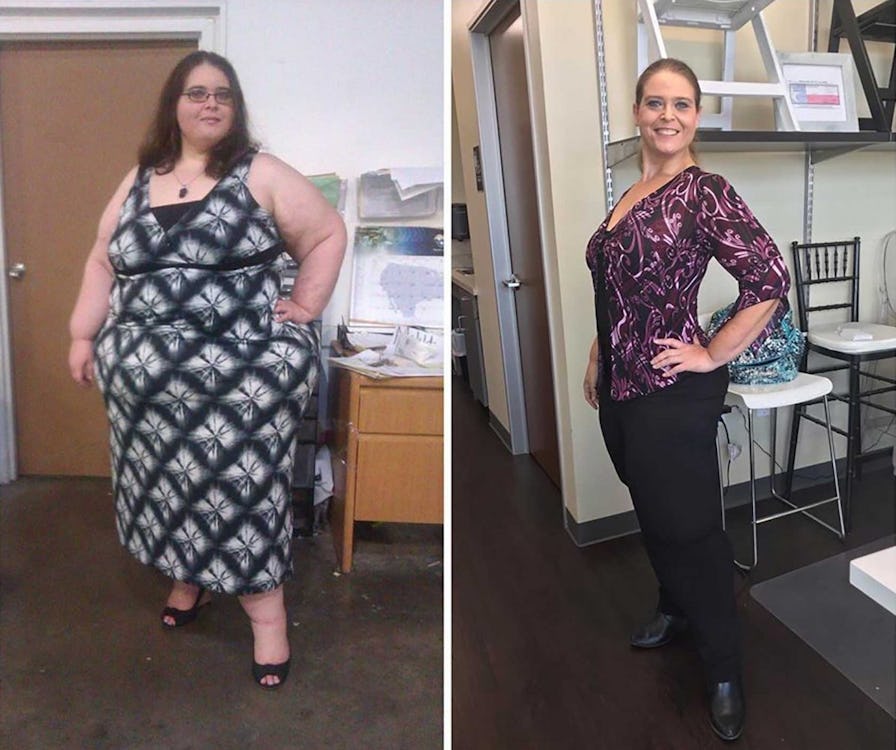

Angi Sanders’ story could be made into an Oscar-worthy Hollywood biopic. The problem, of course, would be finding an actress who could convincingly play her. To blow up to 500 pounds, then lose half your body weight, and go on to be fit enough to beat WWE Superstars in CrossFit WODs… well, even Christian Bale couldn’t do all that for a role.

Sanders, a member of Onnit Gym in Austin, TX, is one of our favorite supporters, and maybe the best ambassador we’ve ever met for how fitness can change your body and your life. What follows is the story of how she did it.

Warning: Some scenes may be too intense for younger viewers.

One of These Things Is Not Like The Other

“For as long as I can remember, I was always on a diet,” says Sanders. “When I was three years old, doctors told my parents that if we didn’t get my weight under control, I would be lucky to live past 28.”

There were six in Sanders’ family, and money was tight, so good nutrition wasn’t a priority in the house. If they ate vegetables at all, it was from a can—and the taste so disgusted Sanders that she learned to avoid all veggies as a result. But it wasn’t the standard American diet or bad genes alone that made Sanders one of the biggest little girls in Arlington, TX.

Sanders never knew her real father (to this day, she doesn’t even know his name). “My sisters were twins, so they had each other,” she says. “My half-brother had my step-dad’s side of the family to rely on. I was the middle kid, and the only one who wasn’t blonde and blue-eyed. So, looking at me, it was like, ‘Which one of these people does not belong?’ I felt like I was alone.”

Food became like family.

“The way she was raised was how I was raised,” says Julie Dudley, Sanders’ mother. “When you celebrate, you eat. When you’re sad, you eat. Angi basically ate her emotions, like many people do. For her, it was just to the extreme. But the way she gained weight, there was no stopping it. We didn’t know how to help her.”

Sanders weighed more than 100 pounds in elementary school. She never learned to ride a bicycle. By junior high, she couldn’t fit into her desks. P.E. teachers excused her from the mile-run fitness test, conceding that it would have taken longer for Sanders to walk the distance than they had time for in class.

“When we went out in public,” says Dudley, “I could see the people stare at her. She held her head up high and ignored them, but I could see the stares, and that hurt me so much. She seemed to be such an enigma to people, but she was a wonderful person. They just couldn’t get past her size to get to know her.”

In spite of her limitations, Sanders never let her body beat her. She was unable to play sports, but she enjoyed reading, watching WWE wrestling, and working with animals by way of the 4-H Club. She became known for having a bubbly personality, a great sense of humor, and a generous heart. Still, the bullying was relentless.

The summer she was 13, Sanders went to science camp. “My group was going up somewhere in an elevator,” she says, “and we got stuck. There was one boy who kept making fun of me, saying the elevator couldn’t lift me, and it was going to fall because we’d reached the weight limit.”

She laid him out with one punch.

“I started to build a rep as someone you don’t mess with,” Sanders says. “I didn’t want anyone to see me hurt.” But as much as she covered up, the blows still got through. She wanted out of her body.

Atkins. South Beach. Weight Watchers… Sanders tried them all. She’d lose weight, and then celebrate by having a cheat meal. Cheat meals turned into cheat days, and then she’d be right back where she started—or even heavier—and totally demoralized.

“I was a binge eater,” says Sanders. “I’d have pizza, soda, and ice cream all in one sitting. I loved to get hot wings and see how many I could eat at once.”

Nutritionists and dieticians were out of the budget, so friends and family came to accept that Sanders was what she was. “After a while, my weight was something that just didn’t get talked about,” she says.

Living Dangerously

In her early 20s, Sanders got a job working for her grandmother in office administration. It paid enough to let her live on her own and keep her utilities on. At 350 pounds, she was as active as she knew how to be.

“Angi wasn’t the positive dynamo she is today,” says Dudley, “but she wasn’t morose either. I think there was denial there, but she wanted to be independent. People suggested to her that she claim disability and get on Social Security benefits, but she said, ‘No, I’m not disabled!’”

“At one point, I tried to get my bigness to work for me,” says Sanders. “A guy I met online suggested I do some modeling—as an SBBW: Supersized Big Beautiful Woman.” She was photographed and videoed in lingerie eating chocolate pies. “It made me sick to my stomach,” she says, “but I was making money doing it. Not my proudest moment.”

Sanders had a boyfriend, and they moved in together. One night, the couple made a pact—if he worked on curbing his drinking, she’d try to slim down.

When she woke up the next morning, he was gone.

Sanders called, waited, and, after a few days, filed a missing person’s report with the police. Nothing. Then, seven months later, he came back. She forgave him, he moved back in, and left her again six months after.

“This time I found a note,” she says. “Actually, two notes.” One said that he couldn’t be with her anymore, but not to feel bad because it wasn’t her fault. “The other one essentially said, ‘Nope, it was all you.’” Whether the second note was just a first draft or the last act of psychological warfare was never clear.

“It’s OK,” says Sanders, who finds it hard to hold grudges. “We’re friends on Facebook now.”

While her personal life was unhappy, Sanders’ health was becoming a dire situation. Though still only in her 20s, she was suffering the effects of a lifetime of obesity. She’d had gallstones for years, but dismissed them as gas. Extreme pain and a trip to the hospital led to having her gallbladder removed. But her weight continued to escalate to the point where she couldn’t find a scale that went high enough to record it. “My doctor told me to go to a feed store to get weighed,” she says.

That’s not to say he wasn’t sympathetic, though. He wrote her a note saying it was OK for her not to wear a seatbelt when she drove. At her size, it would be too restrictive. “Whenever I would get pulled over,” Sanders says, smiling, “I’d show the cop the note and get out of the ticket.”

Since every attempt at dieting had been a failure, Sanders was beginning to open up to more experimental treatments. Her roommates used methamphetamine, and she supposed its stimulating effects might help boost her metabolism. “I told them, ‘I know my personality,’” she says. “‘If I have access to this stuff myself, I’ll have a real problem. So I don’t want to know how to get it. I don’t want to know how to smoke it on my own, and I’m only going to do it when you’re here with me.’”

Her maturity wasn’t reciprocated.

“They ended up robbing me blind for meth money,” says Sanders, “so I kicked them out. And that was the end of my meth experiment.”

No matter, it wasn’t working anyway. “It kept me up for three days,” she says. “I felt very disconnected from my body. I was super focused, but all I wanted to do was stay on the computer. I never lost a pound on it.”

By 2013, Sanders was working for an event rental company that provides tents, tables, and other supplies for big gatherings. The staff was small, and her coworkers became like family. They bought her a membership to the Curves gym chain. Sanders gave it a shot, but the workouts were repetitive, and she got bored.

Then opportunity struck like lightning. Literally. A hurricane caused damages that dramatically increased demand for the company’s services. They made a huge profit supplying equipment for the reconstruction effort.

“My boss sat down with me and said, ‘We want to do something good with the money,’” says Sanders. “‘I don’t want you to die here, so if you want to get a gastric bypass, we’ll pay for it.’”

Sanders had considered the operation before, but she couldn’t get past the idea of someone chopping up her gut and rewiring it. “But he said, ‘We think this is your last shot,’” she says, “and that’s when something clicked in me.’”

Doctors told Sanders she had to lose a substantial amount of weight on her own first, in order to make the already risky procedure safer. It would also go a long way toward proving that the operation wouldn’t be in vain—losing weight by herself would show everyone, including Sanders, that she could take charge of her own body. She did some research on nutrition and started adding fresh vegetables to her diet. “When I discovered them, it was like, ‘A whole new world…” [Sanders begins singing the song from Disney’s Aladdin]. While she had hated the taste of the canned greens she’d grown up with, she loved the fresh variety and learned how to prepare them.

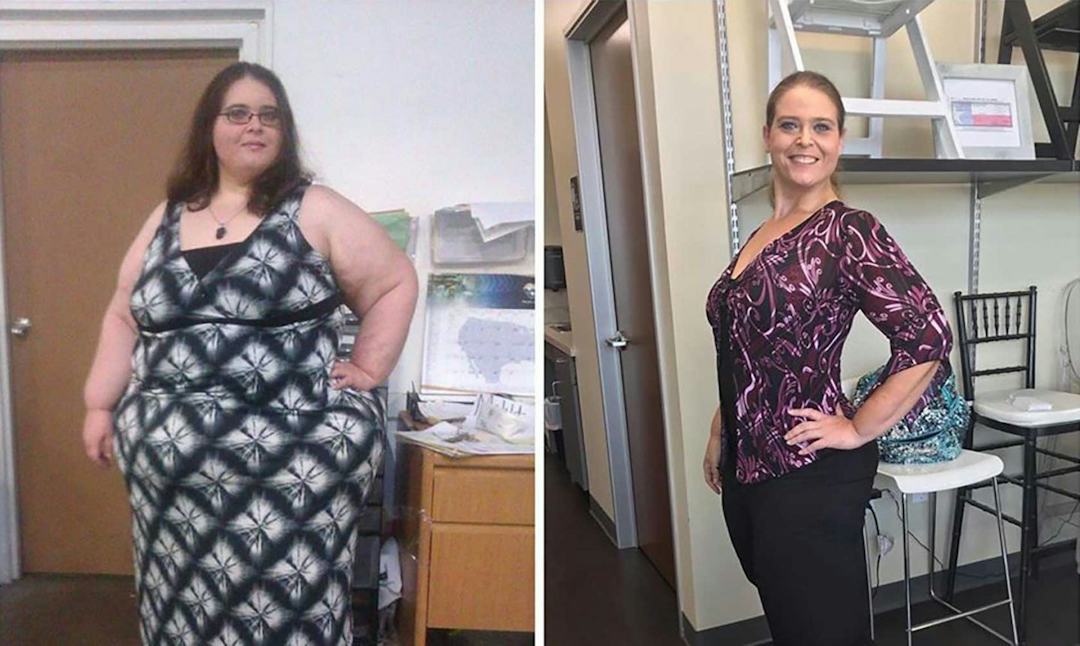

Sanders estimates she was well over 500 pounds at her biggest because she lost about 20 pounds for the operation. “When I could weigh myself on the doctors’ scale, that was amazing to me,” she says. “I was never so happy to see a number that wasn’t just dashes. I was like, ‘Hot damn, I’m 487!’”

Crossing Over

Sanders’s company paid for her to have a bypass operation, but due to her size, her surgeon was still unsure what the best course of action was. Giving Sanders a gastric sleeve—in which most of the stomach is removed—would be (believe it or not) less invasive than a bypass, and would have her under for less time. A bypass reshapes the stomach and then reroutes it directly to the small intestine.

“The doctor said he was going to decide which operation to do once he had me cut open,” says Sanders. “So my first question when I woke up was ‘What did you do to me?’”

The doc opted for the bypass, which reduced Sanders’ stomach to a two-ounce pouch. The change had an immediate and massive impact on her appetite.

“I would take a sip of water and be full,” she says. “For the first time, I wanted nothing to do with food.” She lived off clear liquid protein for the first six weeks post-op. When her appetite returned, she found she couldn’t overeat out of fear of busting her stomach open.

Finally, weight was coming off and staying off. As she was able to move better—and, in some ways, for the first time—Sanders became more active. “Some people try to use gastric bypass as a fix-all,” says Dudley, “but Angi didn’t approach it that way. She said, ‘This is a tool; it’s not the cure.’”

Sanders saw the bypass as a kickstart to being physical in ways she couldn’t be before.

“She got a treadmill in her apartment after the surgery,” says Dudley. “When she felt like she could do more, she went to a gym. And when she wanted to do more than that, she found CrossFit, and then she knew that was where she wanted to be.”

Six months after the operation, Sanders was watching a documentary about WWE Superstar Seth Rollins, her favorite pro wrestler. He said he did CrossFit to stay in shape. She started researching the trend, and soon found herself on the Paleo Diet (an eating philosophy strongly associated with CrossFit). It was just a matter of time before she discovered a CrossFit box in north Arlington.

Sanders had lost 50 pounds by that point, but she wasn’t sure she was fit enough to hack a pro wrestler’s routine.

That didn’t stop her from trying.

She called the CrossFit gym’s head coach, Lennon Simpson (@moarweight on Instagram). “He asked if I could get in my car, drive it, and walk into the gym. I said, ‘Yeah.’ And he said, ‘Then you’re fit enough for CrossFit.’”

Simpson modified some lifts for Sanders, but he didn’t take it easy on her. Of course, she couldn’t do cleans or box jumps or any pressing overhead, but she did deadlifts right away, and walked out of her first workout with two impressions of CrossFit: it was the hardest thing she’d ever done, and she loved it deeply.

“It hurt,” says Sanders, “but it was teaching me so much about who I was that I had never learned anywhere else. We discovered that I’m hypermobile in my joints. Losing weight allowed me to finally express that mobility—I could do big ranges of motion on lifts, and so I was able to improve quickly. I was getting better than I was the day before, and there was no judgment! Doing CrossFit was the first time I ever felt accepted. That’s an addictive feeling.”

Maybe even more so than food.

“Angi was always contagiously positive,” says Simpson. “Most beginners say, ‘I don’t think I can do this,’ or, ‘Gosh, this looks hard.’ But Angi just dove in. The level of enthusiasm and belief she had in herself was inspiring. At the same time, she had a realistic understanding of what her limitations were and knew that workouts would have to be scaled for a while.

“Every workout, she overcame adversity. There were moments where you’d see her sigh, but then she went and did it anyway. She never voiced an ‘I can’t,’ or, ‘I’m not going to make it.’ It’s like she would catch herself thinking a negative thought and immediately shift to, ‘I’ve got this.’ She was never not smiling, dancing, or singing. I never saw her have a bad day. And it was so hard for anybody else to have a bad day when Angi was in class.”

The communal CrossFit environment was undoubtedly a factor in her success. “It gave her a sense that, ‘If these people believe in me, then I can believe in me,’” says Simpson.

Eight months after she started, Sanders wanted to compete in a CrossFit meet. She entered the Festivus Games, a fun-focused competition for novice CrossFitters where the workouts are scaled. Simpson notes that, normally, at any CrossFit contest, most people succumb to fatigue after the first few events and lose momentum. Angi, on the other hand, had to be reined in.

“She was dancing and singing between events,” says Simpson. “I was like, ‘OK, you need to conserve energy. Come sit down.’”

If there’s one thing about CrossFit that critics consistently knock, it’s the reputation it has for consuming its followers in mind, body, and spirit. As Angi went deeper down the fitness rabbit hole, she drifted further away from friends who knew her as someone to party with.

“One thing they don’t tell you about the fitness lifestyle when you get into it is that you’re going to lose people,” says Sanders. Training and diet were her top priorities, and eventually, her friends gave her an ultimatum: it’s us or them.

“I said, ‘I love y’all,’” says Sanders, “‘but I love me more.’”

Bypassing Death

It didn’t take Sanders long to make new, fit friends, who were supportive of her life change. In 2015, when her company asked her to relocate to San Marcos, TX, about 40 minutes south of Austin, she moved. Sanders wasn’t able to find another CrossFit gym with a competitive atmosphere that suited her, but she did find Onnit.

Sanders initially discovered the brand when her hero, WWE wrestler Seth Rollins, appeared on Onnit Founder and Chairman Aubrey Marcus’ podcast. “I thought, ‘What the heck is an Onnit?’” she says. “Then, when I found out more, I knew I wanted to train here.

“I put Onnit on a pedestal,” she says. “Because pro athletes go here. It all seemed so untouchable; I was intimidated! But at the same time, I wanted to prove myself, and I’m the kind of person that if you tell me I can’t do something, not only am I going to do it, but I’ll do it with a smile on my face. After working out here for the first time, I was like, ‘What was I afraid of?’ It’s a gym for everyone.”

Sanders continued to gain strength and lose weight until, in October 2018, she became wracked with extreme abdominal pain. Whatever, she was going to work out anyway. She went for days battling exhaustion and fending off questions from concerned friends who wondered why she looked like death. Attending church on Sunday, she nearly collapsed.

Sanders went to the hospital and was diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia, a condition in which the body can’t absorb iron well—a side effect of her gastric bypass surgery. Doctors told her that a healthy hemoglobin level is 13 grams per deciliter; hers’ was 3.1.

“They were surprised I was conscious at all,” says Sanders. “Let alone able to have a conversation. They told me if I hadn’t gone to the hospital when I did, I would have had only days to live.” Sanders now gets her blood checked throughout the year, and receives iron infusions when she needs to.

The scare didn’t discourage her from training, but it did remind Sanders that there’s life outside the gym too. “She’s so active now,” says Dudley. “She’s hardly ever home except to eat and go to bed. She knows how close she came to dying—in 2018 and all the years before that when she was unhealthy. Her mission now is to live every minute to the fullest, and share it with others.”

Sanders has lost about half her body weight in the past seven years, weighing in at 256 pounds today. In her words: “I lost a linebacker!” Her journey (though far from over) has already inspired her friends, family, and training partners. She even helped her own mother transform her body.

“I was heavy and out of shape,” says Dudley. “I started going to the gym in the summer, when the weather was 100-degrees plus. The first day I went, I got so sick that I had to lie down when I got home. Angi said, ‘Mama, give it two weeks. You’ll notice results after that.’” Dudley stuck with it, with Sanders calling her every day to offer words of encouragement. As predicted, after two weeks, Dudley saw improvements, and has lost 60 pounds in the two years since.

“She still tells me today, ‘No excuses, Mama,’” Dudley says with a laugh.

Fit Enough To Take On Anybody

After surviving anemia, Sanders wanted to make a comeback to CrossFit competition. She looked to her inspiration, Seth Rollins, for guidance, and started training on his branded CrossFit training routine—DeadBoys Fitness.

In November 2019, she competed in the Central Texas Throwdown in Seguin. Though Sanders had always struggled with bodyweight exercises because of her size, she got 18 knee raises in one event, a big PR. In contrast, “the barbell stuff is easy for me,” she says with a grin. “The complex we had to do was only with 105 [pounds].” No skin off the nose of a woman who can deadlift 250 with an overhand grip.

Sanders finished third in her division—her best placing to date.

“They say to never meet your heroes,” she says, “but I don’t agree. I met Seth Rollins at a WWE meet and greet, and I showed him my before picture. I told him he was my hero. He said I was his, and that his proudest moment in CrossFit is knowing the impact he had on me.”

The two have stayed in touch, and Sanders has worked out with Rollins’ DeadBoys group on several occasions, including in 2019 in New York City. Another of her favorite Superstars, Cesaro, a 6’ 5”, 230-pound athletic phenom and multiple-time wrestling champion, joined in. The group performed round after round of overhead squats and jump rope.

“I beat Cesaro!” she says, giddily. “OK, so maybe I was doing a scaled version of the workout, and maybe he had already worked out that day… But I finished before he did!” [See the video below if you need proof.]

Sanders, now 36, says her goal these days is to be a trainer, preferably at Onnit. She’s earned several certifications, and her form on barbell lifts is impeccable. She still has loose skin on her arms and legs from being overweight, but she’s saving up to get it removed (alas, insurance won’t cover it).

When asked if she’s dating, she jokes that she scares guys away. “They don’t want to be the beauty, because I’m a beast,” she says, laughing. “I want someone who is as passionate about fitness as I am. He doesn’t have to be a CrossFitter, but he does have to lift. And it’s OK if he’s not as strong as me. I can train him up.”

)