Summary

– Improving gains in the upper chest requires learning to better isolate the clavicular head of the pec major muscle.

– The best angle to set the bench for incline presses and flyes depends on the dimensions of your own sternum and ribcage.

– The path of motion that your arms travel is a critical factor in upper-chest training technique.

The Best Upper-Chest Workout for Getting Defined Pecs

Whether you’re a recreational gym rat who wants a well-rounded physique, or a bodybuilding/physique/figure competitor looking to bring up weak areas to win a show, there’s one portion of the body’s musculature that’s almost always troublesome to develop: the upper chest.

The pecs are sure to look fuller and more impressive when the region that attaches to the clavicle is more prominent, but for some reason, that part doesn’t seem to respond like the rest of the muscle. To improve this area, there’s one simple prescription that is given time and time again.

You’ve heard it before. “If you want your upper chest to grow, do incline presses and flyes.” The thing is, if you’ve been lifting for any length of time, you’ve probably already tried that. And if that was all there was to it, you wouldn’t be reading this now.

The truth is, putting your bench on an incline isn’t the only consideration for targeting the upper chest. Your individual anatomical structure matters, as well as your biomechanics and ranges of motion on specific exercises.

The new advice for boosting the upper chest is to know your body and train accordingly, and we asked a trio of physique-training experts to tell you how to do that for a more balanced pair of pecs, top to bottom.

What Muscles Are In The Upper Chest?

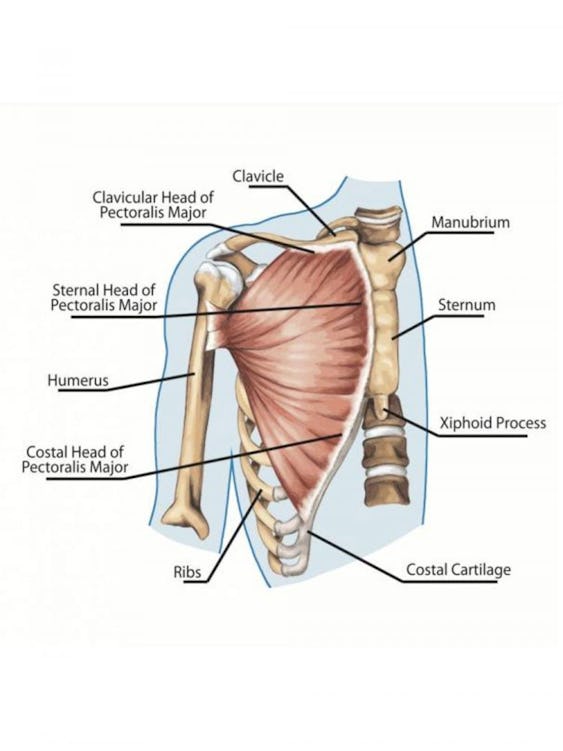

When discussing the upper chest, we’re only talking about one muscle: pectoralis major. However, the pec major consists of three distinct portions of muscle fibers, called heads, and the way they’re arranged determines their function (i.e., the mechanics you need to use to develop them). From the top down, the sections of the pec are:

1. The Clavicular Head (Upper Chest)

The fibers originate on the clavicle (collar bone) and run diagonally downward to attach to the humerus (upper-arm bone).

2. The Sternal Head (Middle Chest)

The fibers start on the edge of the sternum (breastbone) and reach across to attach to the humerus (just below where the clavicular head goes).

3. The Costal Head (Lower Chest)

Fibers run from the cartilage of the ribs and the external oblique muscle to the humerus.

To improve the upper chest specifically, you’ll want to focus mainly on training the clavicular head, but with some emphasis on the sternal head as well, because it covers the upper portion of the sternum (see the diagram above).

Now for the big question: can you really train specific portions of a muscle? For decades, bodybuilders have argued that you can, but scientists have rebutted them, citing the “all or none” principle, which states that a muscle either contracts or it doesn’t—you can’t contract one part of a muscle without the others. Due to the way muscles are innervated, when the signal to contract is sent from the brain, the entire muscle shortens at once.

The truth is, both sides of the debate are correct to a degree. That is, when you work your pecs, you work the whole muscle, but it’s still possible to zero in on specific fibers in the muscle if you set up your training accordingly.

“The ‘all or none’ principle is more around the actual depolarization of the muscle [that] causes it to contract,” says Jordan Shallow, DC, an Ontario, Canada-based strength coach and licensed chiropractor (@the_muscle_doc on Instagram). “There’s no partial contraction—the muscle’s contracting or it’s not. But people conflate that with the idea that a muscle contracts and we can’t put particular tension, or effective tension, across certain fibers… and we absolutely can.”

A study in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research showed as much, with regard to the upper chest specifically. Researchers had subjects perform the bench press at various angles and tested the muscle recruitment for each. Pressing at an incline of 44 degrees resulted in greater activation of the upper-chest muscle fibers than pressing on a flat bench, or one set to 28 degrees of incline. A 2020 study on bodybuilders in the European Journal of Sport Science had comparable findings, with the incline bench press again outperforming horizontal and decline presses for recruiting the upper chest.

However, as we’ll explore below, raising your bench angle is only one component of effective upper-chest training, and research has yet to catch up with what today’s top trainers have learned by experimenting on their clients.

How Do You Target the Upper Chest?

The idea that any chest exercise done on an incline bench hits the upper pecs has been perpetuated for more than a half-century, at least. Arnold credited his outstanding upper chest to incline presses and flyes, and most bodybuilders still swear by them. Indeed, some degree of incline is important to get the clavicular pec fibers working against gravity in the most efficient way, but elevating your bench is only part of the equation.

The key to targeting a certain area of the chest, says Shallow, is “understanding where to look from an anatomical standpoint—that will indicate what pec fibers you’re training. Arm path is going to be a key factor, but sternum angle and ribcage depth are going to be anatomical variations that will drastically affect how you recruit the pecs.”

Kassem Hanson, a trainer of bodybuilders and creator of biomechanics courses for muscle building (available at N1 Education; @coach_kassem on Instagram), echoes Shallow’s comments, particularly with regard to arm path. “The pecs gain their mechanical leverage by using the ribcage as a fulcrum,” says Hanson, “allowing them to pull the arm forward when it’s behind you, and pull your arm across your body when it’s in front. When you put your elbows out wide, you move the pecs away from the ribcage, taking away that fulcrum and leaving you to rely more on your anterior deltoids. This is a common mistake people make when performing an incline press, and also one of the reasons there’s conflicting research on the impact of incline angles on chest recruitment.”

In other words, you can choose any degree of incline that you like, but if you move your arms out too wide on your incline presses, you still won’t target the upper chest effectively.

In addition to arm path, the angle of your sternum and the depth of your ribcage should be considered. Yes, we know that sounds very technical and complex, but it’s not that difficult to assess.

The degree to which you incline your bench depends on your sternum angle and ribcage. “Some people have a very straight up and down chest—a flat sternum angle,” says Hanson, “while others have a steeper angle where the lower portion of their sternum sticks out further. The more angled your sternum, the greater the incline you should use,” up to 45 degrees. “The flatter the sternum,” says Hanson, “the less of an angle—usually around 30 degrees.”

Determining your own sternum dimensions is really as simple as standing in front of a mirror, turning to one side, and taking your shirt off. Look at where your collarbone is versus the bottom of your breastbone and lower ribs. If it’s behind these bones, you’ll probably need a steeper incline than if the two are nearly in a straight line. And if your clavicle is slightly in front of the sternum and ribs, you may need only a few degrees of incline, because your chest is basically on an incline already.

But don’t just rely on bench angle. “One of the most common cheats is people arching their back and completely negating the incline on the bench,” says Hanson. So, once you’ve found the appropriate bench angle, make sure you take advantage of it by keeping your back flat against the bench (even though, alas, it will force you to go lighter and use stricter form).

Remember, too, that the orientation of the pec fibers determines the way you need to move to work the muscle. As you can see in the diagram above, the fibers of the different pec major heads don’t all run in the same direction. The fibers of the clavicular head run at an upward angle (diagonal), not side-to-side like the sternal head. So using an incline bench isn’t as important as making sure your arms are moving along the path that the upper-chest fibers go.

“The clavicular pec is unique in that it originates on the clavicle, not the sternum,” says Hanson. “This gives it more of an upward line of pull, which means you’ll use motions that go low to high. This can be done with a cable, using an incline on a bench, or adjusting your torso position in a machine. Bottom line is, you need to be pressing at an upward angle [to target the clavicular fibers].”

How To Stretch Your Upper Chest

Prepare your chest, shoulders, upper back, and elbows for your upper-chest training with this quick mobility routine from Eric Leija (@primal.swoledier). Perform each move for 2–3 sets of 10–15 reps.

Best Exercises for Building Upper-Chest Strength

Here’s another common debate when it comes to chest training: Are presses or flyes better for hitting the pecs, and, in this case, the upper (clavicular) fibers in particular? Hanson and Shallow agree that there’s no blanket approach that applies to everyone, and both movement types can be beneficial when performed with the proper setup.

“Presses tend to be better for working the lengthened portion of the range of motion,” says Hanson, which is at the bottom of the movement, when your pecs are stretched. “Flyes, [when done with a cable], tend to be better for working the short portion of the range of motion,” when the muscle is nearly fully shortened (such as when your hands come together on a cable flye). “The best option is to use both exercises. Presses tend to have more total pec recruitment, so, when programming, you may do more flye exercises than presses, because one to two good presses will cover it.”

“If I’m doing a flye, I’m going to be able to isolate [the pecs],” says Shallow. “And there’s going to be a certain advantage to being able to isolate the muscle outside of the deltoids and triceps. With the press, you’re going to be able to use more load. That load will be dispersed through the delts and triceps, but if we can set it up properly to make the pecs a prime mover based off the anatomical variants [remember: sternum angle, ribcage depth], we can really make the press a good exercise and challenge the pecs.”

Below are five moves that, if performed properly, will emphasize the clavicular head of the pec major for most individuals. They come courtesy of Hanson and Bill Shiffler, owner of Renaissance Physique, and a competitive amateur bodybuilder.

1. Low-to-High Cable or Band Flye

One of the problems with dumbbell flyes is the lack of tension at the top. As your arms come up from the outstretched position, the resistance drops off, and at the very top, your shoulder, elbow, and wrist joints are stacked, so the weight is just resting on your arms like they’re pillars. You also can’t bring the dumbbells past the midline of your body at the top, because they’ll clang together. Hanson and Shiffler both argue that full range of motion (ROM) is key to developing the clavicular and upper-sternal pec fibers, so pulling the arms across the body is especially important. With cables, you can keep tension on the pecs throughout the entire arc of a flye.

“Free weights give resistance in one direction, which eliminates the ability to get full range of motion,” Hanson says. “A low-to-high cable flye is going to be your best way to get full ROM—especially the range where the muscles are fully shortened.”

Other than offering optimal ROM and biomechanics, the low-to-high cable flye will also provide some much-needed variety to a chest program that includes a healthy dose of pressing movements. “When doing machine and free-weight presses for your middle [sternal] pecs,” says Hanson, “you’ll get some overlapping stimulus in the upper chest, but not in the range of motion you get in a low-to-high cable flye.”

Of course, if you don’t have access to cables, bands can be used as a substitute.

How To Do the Low-to-High Cable or Band Flye

Step 1. Set the handles on both sides of a cable crossover station to the lowest pulley setting. Grasp the handles, and step forward to lift the weights off the stack so that there’s tension on the pec muscles. If you don’t have access to cable stations, use elastic resistance bands as shown, attached to a rack or other sturdy object.

Step 2. Stagger your feet for stability, and let your arms extend diagonally toward the floor, in line with the cables—but keep a slight bend in your elbows. Your palms will face forward. Keep your torso upright and stationary throughout the movement.

Step 3. Contract your pecs to lift the handles upward and in front of your body. The upward path of motion should be in line with the clavicular fibers of the upper pecs—think: diagonal.

Step 4. At the top of the rep, your hands should be touching each other in front of you at around face level, wrists in line with your forearms. Squeeze the top position for 1–2 seconds, and then lower the weight under control, back to the start position.

Sets/Reps: 3–4 sets of 8–12 or 12–15 reps, training close to failure, is Hanson’s general recommendation. (For the best results on this and all the exercises below, periodize your sets, reps, and resistance over time—see Hanson’s comments on this topic below in the Tips for Building More Muscle section.)

2. Converging Incline Machine Press

A converging pressing machine is one where the handles come together as you press the weight, rather than remain static on one path of motion. This allows you to perform a movement that’s more of a hybrid press/flye than what you’d get from most pressing machines, better mimicking the range you’d use during a cable or resistance-band flye and keeping tension on the pecs in multiple planes. When doing a barbell or Smith machine incline press, for example, your hands don’t come together as you press because they’re fixed on the bar, and, as explained earlier, a dumbbell incline press offers no tension in the start/finish position. Though not available in all commercial gyms, a converging press can be a great addition to your training arsenal if you have access to it. (PRIME Fitness USA makes an excellent converging incline press machine, as shown below.)

The upward pressing angle combined with converging handles makes this particular type of incline machine press extremely effective for targeting both the clavicular and upper sternal pec fibers, provided you also achieve an optimal arm path through proper setup.

How to Do the Converging Incline Machine Press

Step 1. Set up for the exercise by raising your upper arms to line up with the direction the clavicular fibers of your pecs run. (This should be roughly 45 degrees out from your sides.) Draw your elbows back and retract your shoulder blades—that’s the bottom end of your range of motion. Now set up in the machine so that you can duplicate that end range position, adjusting the seat height as needed.

Set the incline according to your sternum angle—less steep for a flatter sternum, and closer to 45 degrees for an angled one. If your machine’s incline isn’t adjustable, this may require scooting your butt forward on the seat to (ironically) take away some of the incline. If your machine allows it, you can use a neutral (palms facing in) grip, which may feel better for your shoulders or allow a better angle of the arms to hit the upper pecs.

Step 2. Unrack the weight to put tension on the pecs, and then press the handles up to full elbow extension, focusing on driving up and in. Hanson cues the movement by telling clients to think about bringing their armpits up into their clavicles on each side, so you squeeze both ends of the clavicular head together.

Step 3. Lower the weight under control. Stop when your hands are just above chest level (don’t let the weight rest on the stack between reps).

Exercise Variations: To target more of the sternal fibers that make up the middle/upper portion of the pecs, the upper-arm position will be slightly different than what’s described above. Because the sternal fibers run more or less side to side, you’ll want the arms to line up with those fibers. That means your elbows will be up a bit higher and pointed out to the sides, with a path of motion going from out to in, straight across the body. (This is shown better in the first variation used in the video above.)

Hanson shows both variations of the incline converging machine press (sternal and then clavicular pec emphasis) in this video.

Sets/Reps: 3–4 sets of 6–8 or 10–12 reps, training close to failure.

3. Dumbbell Incline Press with Semi-Pronated Grip

According to Hanson, a relatively narrow grip better targets the upper chest because it allows the elbows to stay in closer to the body, and that prevents the front delts from taking over the movement (as is the case on presses done with a wide grip). If you’re pressing with a barbell, he recommends a grip just outside shoulder-width. “However,” he says, “narrower arm paths work better with a neutral grip [palms facing each other] or semi-pronated grip [palms somewhere between facing each other and facing straight forward],” whichever is more comfortable for you. This being the case, dumbbells are a better option than a barbell for targeting the upper pecs.

With dumbbells, you can easily assume a neutral or semi-pronated grip, whereas a barbell locks your hands in a fully pronated position, and, Hanson says, “encourages the elbows to flare out.”

How to Do the Dumbbell Incline Press with Semi-Pronated Grip

Step 1. Set an adjustable bench to a 30–45-degree angle, depending on your sternum angle. Grasp a pair of dumbbells and lie back on the bench, making sure your entire back is in contact with it—do not arch your back so that it causes your lower back to rise off the pad.

Step 2. Start with the dumbbells just outside your shoulders, elbows bent, and your forearms/wrists in a semi-pronated (or neutral) position.

Step 3. Keeping your elbows pointing at about 45 degrees, press the dumbbells straight up until your arms are just shy of full lockout. Lower the dumbbells back down under control, until they’re just above and outside your shoulders.

Step 4. As you press and lower the dumbbells, establish a natural, comfortable wrist position—something between neutral and semi-pronated. The dumbbells give you the freedom to adjust mid-set.

Sets/Reps: 3–4 sets of 6–8 or 10-12 reps, training close to failure.

4. Swiss-Bar Incline Press

This exercise, also recommended by Hanson, is more or less the barbell version of the incline dumbbell press described above. A Swiss bar (aka “football bar”) is a specialized barbell with handles that offer neutral and sometimes semi-pronated grips. While not typically available at big box fitness clubs, if you can find a hardcore powerlifting or bodybuilding gym, or athlete training facility that has one of these bars, it’s worth trying out.

With the Swiss bar incline press, you get the upper-pec biases of the angled bench and neutral grip with the added bonus of greater overload placed on the muscles because you’re using a barbell (which is more stable than pressing a pair of dumbbells).

If your sternum is fairly flat, go with a 30-degree angle. If the top of the sternum is behind the lower ribs (an inverted angle), go with 45 degrees.

How to Do the Swiss-Bar Incline Press

Step 1. Rack a Swiss bar (or football bar) at an incline bench press station. Lie back on the bench and grasp the neutral or semi-pronated grips (palms facing each other or a little angled) with hands just outside shoulder-width.

Step 3. Unrack the bar, and lower it under control to your upper chest with your elbows tucked in close to your sides, about 45 degrees from your torso.

Step 4. When the bar touches your upper chest, explosively press it straight up to full arm extension, keeping your elbows tucked in as you press.

Sets/Reps: 3–4 sets of 6–8 or 10–12 reps, training close to failure.

5. Incline Dumbbell Flye

The key to targeting the upper chest with a dumbbell flye is the same as with the low-to-high cable flye: establish an arm path that moves in the same direction as the diagonal fibers of the clavicular pecs. Doing a flye with the torso at an inclined position should automatically help you.

If you were doing a flye on a flat bench, the upper arms would more or less be moving in the same direction as the sternal fibers—straight horizontal, not diagonal. (The exception here would be someone with a sternum angle where the clavicles are significantly further forward than the lower ribs, which would put you at a natural incline even on a flat bench.)

An incline bench, on the other hand, puts you at such an angle that the same flye motion has your upper arms moving diagonally upward in relation to your torso—same as the clavicular fibers. Will there still be some sternal fibers activated? Of course. But as mentioned earlier, these fibers reach into the upper chest area, so no harm there.

As for what bench angle to use, again, assess your sternum angle. If your sternum is fairly flat, go with a 30-degree angle. If the top of the sternum is behind the lower ribs, use 45 degrees. As mentioned above, a free-weight flye isn’t quite as effective as one done on a machine or with cables/bands, because the resistance is reduced at the top, but it’s a solid option for those who don’t have access to fancy equipment.

How to Do the Incline Dumbbell Flye

Step 1. Set an adjustable bench to a 30–45-degree angle, depending on your sternum shape. Grasp a relatively light pair of dumbbells, and lie back on the bench.

Step 2. Start with your arms fully extended, perpendicular with the floor, and the dumbbells directly above your upper chest, palms facing each other.

Step 3. With a slight bend in the elbows, lower the dumbbells by opening your arms. Lower the weights slowly with control until you feel a stretch in your pecs.

Step 4. Contract your pecs to lift the dumbbells back up and together, maintaining the slight elbow bend throughout. “Really focus on the stretch at the bottom of the rep, and squeeze the pecs at the top,” says Shiffler.

Exercise Variation: The incline flye can also be done with cables, placing an incline bench in the middle of a cable crossover station and using handles at the lowest pulley settings.

Sets/Reps: 3–4 sets of 8–12 or 12–15 reps, training close to failure.

Upper-Chest Exercise Alternative

If you’re training at home without the luxury of any equipment, you can resort to the classic pushup done with your feet resting on an elevated surface. “This is pretty similar to an incline press in the way it targets the upper chest,” says Shiffler, “with the added benefit of targeting some stabilizer/core muscles while you’re at it.”

Pushup with Feet Elevated

As with other variations, adjust the height of your feet based on your sternum angle—body at around 30 degrees to the floor if you have a flat sternum, and feet up a little higher if your sternum is angled.

How to Do the Pushup with Feet Elevated

Step 1. Place your hands around shoulder-width on the floor, and raise your feet behind you on a bench, box, or other stable surface. Tuck your tailbone slightly so that your pelvis is neutral, and brace your core. Your body should form a long, straight line.

Step 2. Lower your body, tucking your elbows about 45 degrees from your sides, until you feel a stretch in your pecs. Press yourself back up, allowing your shoulder blades to spread at the top. This action is another advantage of the pushup—pressing exercises done on a bench restrict your scapular movement, while the pushup allows these muscles to work naturally to stabilize your shoulders.

Tips for Building More Muscle

Here are a few more tips, courtesy of Hanson, for getting the greatest possible upper-chest growth.

Sets and Reps

“You want to train the pecs with both low and high reps—not necessarily in the same workout, but through periodization,” says Hanson. That is, plan changes in your training over time to keep the muscles responding. “A lot of people perform too wide a range of reps in the same workout, which can confuse the body in terms of the appropriate adaptation.”

Hanson generally recommends doing no fewer than 4 reps per set on presses and no fewer than 6 reps per set on flye movements, unless you’re training for a specific strength goal. “You could spend one block of training doing presses in the 6–8 rep range and flyes in the 8–12 range,” he says. “Then switch to 10–12 and 12–15 reps, respectively, in the next block.”

Tempo

When it comes to the speed with which you perform your reps (which trainers call tempo), Hanson says the biggest key is making sure you control the resistance during your sets. Don’t bounce the weights up, or let them drop as you lower down on a rep.

“Presses can be performed with a wide variety of tempos,” says Hanson. “But you shouldn’t be going super slow or throwing the weight up explosively. For flyes, you’re using your whole arm as a lever, so controlling the eccentric [negative/lowering portion of the rep] is much more important for safety and stimulus.”

Advanced Techniques

The more experienced you get, the more creative you can get with tempo. For pressing exercises, “adding a two-second pause or an extra quarter-rep at the bottom can be a great variation in stimulus,” says Hanson. “You’ll get more sore with those techniques, and they increase volume, so consider dropping a set or two when using a more advanced tempo, and then progressing back up.”

With cable flyes, Hanson recommends a one to two-second squeeze in the end position, when your hands are close together. “Because you fatigue in the shortest part of the range of motion first, an advanced technique is to use a pause in your early sets and decrease or remove it in the later sets,” he says. This way, you can keep up your reps and not be limited by the weakest part of the movement [as you get tired].”

Sample Upper-Chest Workouts

(See 01:28 in the “Best Upper-Chest Workout for Defined Pecs” video at the top of this article)

Here are two sample workouts you can do that prioritize the upper chest. You can use either routine or both of them in the same week (space them out by four or five days). There are only two upper-chest exercises in each workout, and that’s all you need. Finish out each workout with some work for the middle and/or lower pecs, shoulders, or triceps.

Sample Upper-Chest Workout A

1. Dumbbell Incline Press with Semi-Pronated Grip

Sets: 2 Reps: 6–8

(See 01:49 in the video.)

Perform as many warmup sets as you need until you reach a weight that’s heavy enough for your first work set. Do 6–8 reps to failure, or close to failure, and then reduce the load by 20% for your second set, and aim for the same rep range.

2. Low-to-High Cable or Band Flye

Sets: 2 Reps: 10–12

(See 03:10 in the video.)

Sample Upper-Chest Workout B

1. Neutral-Grip Incline Bench Press

Sets: 2 Reps: 5–7

(See 04:54 in the video.)

Perform as many warmup sets as you need until you reach a weight that’s heavy enough for your first work set. Do 5–7 reps to failure, or close to failure, and then reduce the load by 20% for your second set, and aim for the same rep range.

2. Pushup with Feet Elevated

Sets: 2 Reps: 8–12

(See 06:04 in the video.)

)