Nothing sparks a debate like nutrition. One day you’re told something is unhealthy, the next it’s not, and it seems like just when you’ve stocked your pantry with the right food it’s back on the naughty list again.

In short, you’re tired of being jerked around. And we don’t blame you. That’s why we were infuriated by the American Heart Association’s (AHA) position statement, “Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease,” which attacked saturated fats—and coconut oil specifically. Published last week, it outrageously stated the following: “Because coconut oil increases LDL cholesterol, a cause of cardiovascular disease, and has no known offsetting favorable effects, we advise against the use of coconut oil.”

And that was just the beginning. In a follow-up article announcing the report on the AHA’s website, the lead author of the advisory was quoted as saying, “I just don’t know” who would recommend consuming coconut oil. He went on to add that “there’s nothing wrong with deep frying [foods] as long as you deep fry in a nice unsaturated vegetable oil.”

Shocked? You have a right to be. Even the AHA called that statement “surprising” in the article.

But the madness didn’t stop there. USA Today (presumably looking for a clickable headline) pounced on the news, releasing a story entitled “Coconut Oil Isn’t Healthy. It’s Never Been Healthy,” asserting that coconut oil is dangerous because “it’s almost 100% fat” and citing the AHA’s recommendation to limit saturated fat to a mere six percent of your daily caloric intake.

Onnit says: enough is enough.

The following is our effort to clear up some misconceptions about the cloudy oil so many people have grown to rely on in their cooking and supplementation. Spoiler alert: we’re not going to conclude that coconut oil is the healthiest food on earth and you should eat it by the jarful. But we’re pretty sure that by presenting you a more complete picture of the evidence surrounding coconut oil, saturated fat, and health, you’ll be able to decide for yourself the truth about coconut oil and your heart.

First Of All, The AHA Is A Little Whack

It’s pretty clear from the broad statements made in the AHA’s report that it’s only interested in furthering its long-held agenda that saturated fats are unhealthy—they’re not taking into account newer research with contrary findings.

A little more background on the report: it basically says that, based on numerous papers that have come out over the past several decades (some of them are, ahem, 60 years old), saturated fat increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and should therefore be limited in the diet. In its place, the researchers recommend eating more unsaturated fats—particularly polyunsaturated fats, such as those found in popular vegetable oils.

The AHA advisory wasn’t spurred by the emergence of a new study, but rather (by the researchers’ own admission) was done in reaction to a bunch of other ones they didn’t like—specifically, a 2014 meta-analysis (a review of multiple studies) from the Annals of Internal Medicine that found that there isn’t evidence to support recommendations to consume high amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids and low amounts of saturated fat.

The AHA report clearly states that the researchers didn’t look at “clinical trials that compared direct effects on cardiovascular disease of coconut oil and other dietary oils.” So if they didn’t specifically study coconut oil’s effect on heart health versus other types of oil, how can they conclude that it’s more dangerous? Their answer: because it increases LDL cholesterol like other sources of saturated fat. We’ll argue this point further down, but it should stand out to you right away that making a blanket statement about one food based on its similarity to other foods is unfair.

The studies they did cite only showed that coconut oil raised cholesterol, but looking deeper, we found that they showed coconut oil raised not just LDL cholesterol (the so-called “bad” kind) but HDL cholesterol as well. The truth is, science is still inconclusive on whether saturated fat raises LDL cholesterol at all, but doctors and nutrition experts uniformly agree that increases in HDL have a positive effect on cardiovascular health.

So why does the A.H.A. have its head so far up its A.S.S? For one thing, it has two members of the US Canola Association (as in canola oil, the so-called “heart healthy” polyunsaturated fat) on its nutrition advisory panel, along with numerous other corporate influencers. Does that sound like bias to you?

And the research the AHA uses to back its position isn’t above suspicion either. A 2015 New York Times article raises the point that nutrition policies have long relied on epidemiological studies—those that observe groups of people for years. “Even the most rigorous epidemiological studies suffer from a fundamental limitation,” the article goes. “At best they can show only association, not causation. Epidemiological data can be used to suggest hypotheses but not to prove them. Instead of accepting that this evidence was inadequate to give sound advice, strong-willed scientists overstated the significance of their studies.”

The piece goes on to reveal that much of the epidemiological research that government organizations base their nutrition guidelines on comes from studies run by Harvard’s school of public health (and lo and behold, that’s just where the lead scientist behind this latest advisory report was from). Trouble is, as the National Institute of Statistical Sciences found in 2011, Harvard’s most important findings have yet to be reproduced in clinical trials. In other words, get a bunch of people in a controlled study where the scientists feed them saturated fat and observe the outcome, and the results don’t match what the AHA has said.

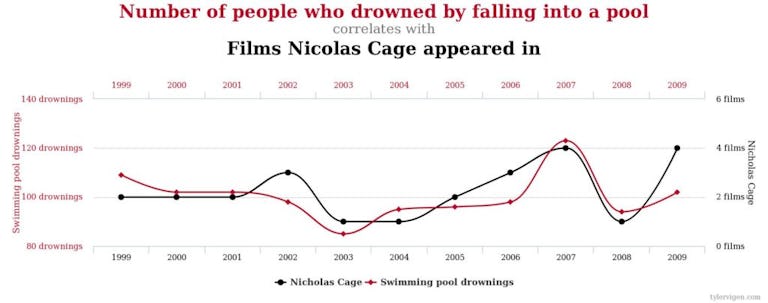

To further the point about the danger of confusing correlation with causation, Diana Rodgers, R.D., wrote on her own site sustainabledish.com the following in response to the AHA report: “The number of films Nicolas Cage has been in correlates with the number of people who have drowned falling into a pool.” She even created this nifty graph below to illustrate the concept.

So maybe every time Nic Cage releases a movie someone dies. Does that mean we should lock up Nic Cage? (If you’ve seen The Wicker Man, you might vote yes, but obviously he’s not a killer.)

Saturated Fat Does Not Equal Cardiovascular Disease

Here’s a look at the few clinical trials that have been done to show the relationship between saturated fat and heart disease (or lack thereof).

– In 2006, research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association looked at 48,835 women who reduced their total fat intake to 20% of calories and increased consumption of fruits, vegetables, and grains in place of fat. After more than eight years, the diet had not lessened the risk of heart disease, stroke, or cardiovascular disease, leading the researchers to conclude that “more focused diet and lifestyle interventions may be needed to improve risk factors and reduce cardiovascular disease risk.”

– In 1989, the Minnesota Coronary Survey followed nearly 10,000 men and women split into two groups to see if a lower-fat diet reduced cardiovascular risk. One consumed a diet with nine percent saturated fat and the other a diet with 18% saturated fat over four and a half years.

Were the people who ate double the saturated fat of the experimental group twice as likely to die? No. In fact, despite a 14.5% reduction in cholesterol levels in the low-fat dieters, the group who consumed high amounts of saturated fat proved to be healthier. There was no reduction in factors that damage the heart, or total deaths, in the experimental low-fat group.

One of the most frequently cited studies to support the idea that saturated fat is bad took place in a Finnish mental hospital in 1972 (we couldn’t make this shit up). Researchers replaced milk fat in patients’ diets with soybean oil, butter with margarine, and had them eat more root vegetables and less meat and eggs. After 12 years, there was a significant decrease in coronary heart disease death in men, but not in the women. However, the results still aren’t cut and dried.

Some of the study subjects were also prescribed “cardiotoxic medications,” which, according to the Ancestral Weight Loss Registry, a non-profit group that tracks people’s health changes on higher-fat diets, “warrants careful interpretation of the findings and likely diminished the external validity of these observations.” If these mentally-impaired Finns were taking drugs that hurt their hearts, maybe meat and eggs weren’t doing the damage after all.

Our Scandinavian friends were at it again in the 70s with the release of the Oslo Diet-Heart Study, another experiment the AHA proudly uses to buttress its anti-saturated fat argument. In this case, a single researcher asked local doctors to find subjects who were at high risk for heart disease or had had heart attacks already. He then divided them into two groups and put one on a diet low in saturated fat and high in polyunsaturated fats, while the control subjects stuck with the standard Norwegian diet. After five years, the experimental group was determined to have a lower incidence for heart attacks.

But here’s the thing. The low saturated fat-dieting Norwegians also received “continuous” nutrition counseling and supervision, while those who ate their normal diet were left to their own devices. That’s kind of like giving one class of fifth graders the answers to a test and giving another one the wrong books to read to cram for it. According to an article by investigative journalist Gary Taubes, “This is technically called performance bias and it’s the equivalent of doing an unblinded drug trial without a placebo… We would never accept such a trial as a valid test of a drug. Why do it for a diet?”

Now let’s look at some epidemiological studies just for the hell of it. Let’s see how saturated-fat eaters hold up over the long haul outside of labs and in the real world.

– A 2010 meta-analysis in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that looked at 21 different studies is the grand-daddy of them all. Between five and 23 years, 347,747 subjects were followed, 11,006 of whom developed cardiovascular disease or strokes. The researchers’ findings couldn’t have been more clear: “Intake of saturated fat was not associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular heart disease, stroke, or cardiovascular disease… Consideration of age, sex, and study quality did not change the results.”

– In 1998, a paper from the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology examined people in up to 35 different countries around the world looking for a direct link between dietary fats and cardiovascular disease. “The positive ecological correlations between national intakes of total fat and saturated fatty acids and cardiovascular mortality found in earlier studies were absent or negative in the larger, more recent studies,” the authors wrote, concluding that “the harmful effect of dietary saturated fatty acids and the protective effect of dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids on atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease are questioned.”

Saturated Fat: A Good Guy?

By this point, you’re hopefully at least allowing the possibility that saturated fat isn’t the heart-clogging killer some have made it out to be. But might it actually be healthy? Can it have benefits for your heart? There’s a pile of research that says it can, based largely on the idea that saturated fat raising cholesterol is a good thing, not a bad one. Here’s how saturated fat and cholesterol work in the body.

Most nutritionists believe saturated fat intake raises cholesterol in the body. Cholesterol is a fat-like substance your body uses in its cells and to make hormones. It’s undeniably essential for good health, but the problem comes with the vessel it uses to move around the body—lipoproteins. These are proteins that carry cholesterol, fat, and fat-soluble vitamins through your bloodstream. High levels of lipoproteins are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, but the relationship isn’t causal. Having “high cholesterol,” as this condition is called, doesn’t automatically mean your heart will get sick.

Scientists acknowledge that the type of cholesterol your lipoproteins carry around makes a critical difference to your health. High-density lipoprotein (HDL cholesterol) is the “good” kind and low-density lipoprotein (LDL cholesterol) is often labeled the “bad,” with high levels of LDL specifically being linked to cardiovascular disease. But labeling LDL all bad is an oversimplification.

LDL particles come in different sizes. Small, dense particles get stuck in the arteries, clogging them and increasing the risk of heart attacks and strokes. However, larger, “fluffier” particles may not pose the same danger. According to research found in Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, large LDL particles were not found to be associated with an increased risk of ischemic heart disease in men, and that the cardiovascular risk LDL cholesterol does pose is related to levels of its small particles. Other work in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that LDL particles were significantly smaller in coronary artery disease cases, and the findings “support other evidence of a role for small, dense LDL particles” as a cause of hardening of the arteries.

And here’s where saturated fats shine. They increase the size of LDL particles, potentially making them safer.

In 1998, the American Society for Clinical Nutrition reported that subjects who consumed high-fat diets (46% of calories), including a high saturated fat intake, increased the concentration of the larger particles of LDL cholesterol. Another trial in 1997 found in the Journal of the American Medical Association discovered that intakes of all types of fat, including saturated, reduced the risk of stroke in men.

If anything, this so-called nutritional devil should be helping your heart—not turning it into a time bomb.

But, to be totally honest, science still can’t prove that LDL cholesterol is a good indicator of cardiovascular disease at all. A 2009 study in American Heart Journal looked at lipid levels in people hospitalized with coronary artery disease. Out of 231,986 patients in 541 hospitals, almost half had “normal” LDL cholesterol levels—less than 100mg/dL. On top of that, more than half had low HDL cholesterol (less than 40mg/dL when 60 and above is optimal).

Coconut Oil IS Healthy. It’s ALWAYS Been Healthy

Now let’s look beyond saturated fats to coconut oil specifically. The fat in coconut oil is indeed saturated (82% in fact), but to say it has “no offsetting favorable effects” is blatantly false.

A 2009 study in Lipids compared the effects of coconut oil consumption versus soybean oil in obese women. The coconut oil group ended up having higher HDL cholesterol levels and an improved ratio of LDL to HDL. The soybean oil group? Their total cholesterol went up, as did their LDL, and their HDL levels went down. As a result, their ratio of LDL to HDL got worse!

Not only did the coconut oil prove to be more heart healthy, the women lost weight while taking it.

Other studies have shown that coconut oil increases metabolic rate, at least in the short term. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition compared coconut oil ingestion as part of a high-fat diet (40% of calories from fat, 80% of those from coconut oil) to the fat in beef tallow. After seven days, the coconut oil subjects saw a 4.3% greater boost in metabolism.

One of the special properties in coconut oil is its medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs), a type of saturated fat that the body seems to burn quickly for energy. The Journal of Nutrition found that subjects who consumed 10g of MCTs versus 10g of long-chain fats experienced more pure fat loss after 12 weeks. Remember, the study looked at MCTs, not coconut oil, but it’s not hard to imagine coconut oil having similar potential due to its MCT content.

Of course, coconut oil has been widely used by various cultures for ages for its anti-bacterial and anti-viral properties, as well as for its macronutrient value.

Two of these cultures are Pukapuka and Tokelau, which are islands in the south Pacific. Both populations consume diets high in saturated fat—particularly from coconuts—but low in sugar. According to the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, “Vascular disease is uncommon in both populations and there is no evidence of the high saturated fat intake having a harmful effect.”

There’s also the people of Kitava, an island belonging to Papua New Guinea. People there still live much the way they did 100 years ago, and, according to the Journal of Internal Medicine, living has been “uninfluenced by western dietary habits.” Coconut is a dietary staple, and yet “stroke and ischaemic heart disease appear to be absent in this population.”

How To REALLY Lower Your Risk For Cardiovascular Disease

There are no guidelines for how much saturated fat or coconut oil to include in the diet that can apply to everyone. Neither means certain death if you consume it, but at the same time we can’t guarantee that you—personally—can load up on the stuff without some risk. However, rather than demonize natural foods that offer huge potential health benefits, we advise looking into various lifestyle factors that have a lot more impact on your heart health.

Watch your polyunsaturated fats. Fish oil is widely recognized as a safe and effective supplement, but the polyunsaturated fats in processed vegetable oils like soybean and corn—yes, the very ones your friends at the AHA want you to eat more of—have been shown to be dangerous many times over. The difference is that fish oil is a source of omega-3 fatty acids, which fight inflammation, while omega-6 fatty acids promote it. Some inflammation is OK and even necessary for health, but when the ratio of omega-3 to 6 gets out of whack in your body—which can easily happen with overconsumption of vegetable oils—the imbalance gives rise to numerous health problems.

The British Journal of Nutrition published a meta-analysis that revealed the effects of polyunsaturated fats on cardiovascular disease risk when used as an intervention for better health. Some of the trials analyzed looked at what happened when polyunsaturated fats replaced saturated fats in the diet. The conclusion: “Advice to specifically increase polyunsaturated fat intake… is unlikely to provide the intended benefits, and may actually increase the risks of cardiovascular disease and death.”

Think about this: certain chronic diseases that are now epidemics were a rare occurrence until the mid-20th century. Heart disease started becoming a national problem in the 1930s, obesity in 80s, and diabetes in the 90s. According Dr. Stephan Guyenet, author of The American Diet, the rise of these highly preventable health woes coincides with the gradual replacement of saturated fats in the American diet with polyunsaturated fats—and the switch from butter to margarine in particular.

Ever hear of the Framingham Study? It’s one of the most long-term experiments in history, in which researchers began to follow residents of Framingham, Massachusetts, in 1948 for clues as to how lifestyle affected heart disease over decades. In the late 1960s, the study leaders noted how much margarine some of the men were eating, and, after 10 and 20 years, checked back in on them. They found that margarine intake increased the risk of coronary heart disease. Incidentally, they found that butter did not.

Be active and healthy. Eating better is one thing, but there’s a lot to be said for the health-promoting effects of exercise. Consider the Maasai tribe of Tanzania. Like the island people described above, their diets are high in saturated fat but the incidence of cardiovascular disease among them is low. One aspect of their lives that’s thought to be a factor in keeping heart disease rates down is their tremendous activity levels—they burn some 2,500-plus calories a day over their basal metabolic requirements (the minimum needed to stay alive). Their blood pressure was also lower than that of a neighboring tribe. Researchers for a study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine believe that any damage the Maasai diet might do to their hearts is offset by their energy expenditure.

Obviously, taking overall good care of yourself should be your primary focus for avoiding all health problems. For example, if you smoke, quit. Whatever foods you choose to eat, make sure most of them can be found in nature, and don’t overeat. A review by The American Society for Nutrition entitled “Saturated Fat, Carbohydrate, and Cardiovascular Disease” recommends that any dietary effort to reduce cardiovascular disease risk should “primarily emphasize the limitation of refined carbohydrates”—read: cut back on sugar and breads—and weight loss.

Relax. No one can argue that one food—or nutrient—eaten in moderation can be harmful, let alone deadly. “We don’t eat ingredients,” says Chris Mohr, Ph.D., R.D., “we eat foods, and an overall diet. One thing will never make or break you, and that goes for coconut oil.”

Ben House, Ph.D., C.N., adds that “body composition, fiber intake, thyroid function, and infections are probably much bigger issues than you using one or two tablespoons of coconut oil a day. But these topics are complicated and can’t be nicely wrapped in a few-paragraph bow,” as the AHA did with its saturated fat indictment.

And one more thing about the AHA’s advisory. House says, “Don’t share these types of articles or give them any mind. Don’t fall for the sensationalist clickism.”

It’s bad for your heart.

For further reading, check out:

1. “Vegetable Oils, (Francis) Bacon, Bing Crosby, and the American Heart Association,” by Gary Taubes.

2. “Why Coconut Oil Won’t Kill You, But Listening To the American Heart Association Might,” by Diana Rodgers, R.D.

3. “Saturated Fats and Heart Disease: The Clinical Trials,” the Ancestral Weight Loss Registry.

4. “Is Saturated Fat Bad For Me?” Examine.com.

5. “Big Sugar’s Sweet Little Lies,” by Gary Taubes and Cristen Kearns Couzens.

6. “50 Years Ago, Sugar Industry Quietly Paid Scientists To Point Blame At Fat,” by Camila Domonoske.

7. “Oxidized Cholesterol & Vegetable Oils Identified as the Main Cause of Heart Disease,” University Health News.

8. “The Government’s Bad Diet Advice,” by Nina Teicholz.

9. “Top 9 Biggest Myths About Dietary Fat and Cholesterol,” by Kris Gunnars, BSc.

THO #135 Coconutgate with Aubrey Marcus | Total Human Optimization Podcast

USA Today via the American Heart Association put out an article this week claiming that Coconut Oil is not healthy… and that it never was! In this episode, we dissect and discuss their claims and their stance behind… vegetable oil.

)