A twangy acoustic guitar starts playing behind me and a country voice begins to sing: “If I could have a beer with Jesus…” I’ve been exploring the 40-acre BMF Ranch in Edgewood, New Mexico, and now, sensing from the music that its owner is beginning to unwind, I follow the sound inside the sprawling ranch house. I pass a plaque in the kitchen titled “The Code of the West,” a frontier-style 10 Commandments that outline how Donald Cerrone lives his life.

I make note of them and walk past a taxidermied rattlesnake and trophy antlers to find Cerrone—a man who, with one more win, ties the legendary Georges St. Pierre for the second most victories in UFC history. He’s redoing the trim on a windowsill in his guest bedroom.

Take Pride in Your Work

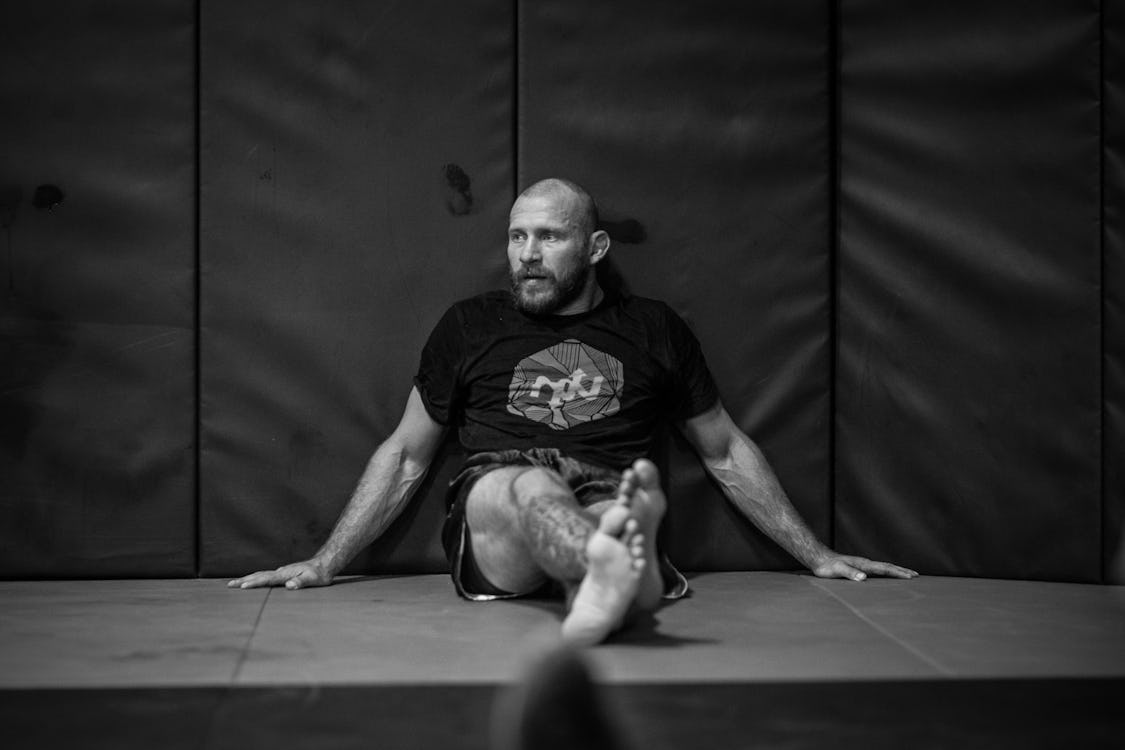

Cerrone is the kind of fighter that hardly exists anymore. He’s willing to fight anyone, anytime, anyplace, and while that’s a macho cliché, Cerrone actually has it written on his sandals. “Any” appears on the right shoe, while “one,” “time,” and “place” are printed on the left. (Probably not an item available at your local Walmart.)

Cerrone, whose mixed martial arts record is 31–7, is arguably the most exciting fighter in the UFC, and certainly the most active, logging four bouts per year since 2013. He’s renowned for taking fights on only a few days’ notice, winning them more often than not. He’s fought practically everyone who is anyone—Nate Diaz, Anthony Pettis, Eddie Alvarez—in both the lightweight and welterweight divisions.

No matter what you look for in a fighter as a fight fan, Cerrone has it covered. You want raw savagery? Watch his merciless leg kicks on a downed Myles Jury at UFC 182. Heart and gameness? See his recovery from an early attack by Melvin Guillard at UFC 150, when he came back with a head kick to set up the KO. Most recently, he enunciated his technical prowess with the awe-inspiring jab, cross, hook, and kick combination that gave Rick Story—his last victim at UFC 202—an unhappy ending. Cerrone has earned bonus payments for outstanding performances a record 18 times—the most in the history of Zuffa (former parent company of the UFC and its offshoot WEC).

He’s the rare type of athlete who would rather lose fighting his way than eke out a win by any means necessary, and he refuses to fight conservatively for fear of disappointing fans. By all logic, Cerrone should be only a win or two away from a welterweight title shot.

And yet the man dubbed “Cowboy” because of his straw hats and flair for riding bulls in rodeos seems, at the moment at least, far more interested in finding his tape measure than in talking about his next opponent. (Cerrone is set to face Matt Brown at UFC 206 on December 10.)

“I always thought supplements were bullshit, but I tried them for 20 days and damn, man, I honestly feel the difference. I wake up not as sore. I have more drive to train. When I take the Total Strength and Performance and the Shroomtech, it gives me energy without Red Bull or candy. Experimenting with Alpha BRAIN® and New MOOD® have helped too. “My mood is more consistent. I’m more focused. I feel fucking good.”

I ask him about the street fights, his grandmother who at age 80 still attends all his fights, and how he came to own this massive expanse 30 minutes east of Albuquerque. Flies that have wandered in from the stable just outside the front door to the house (where Cerrone keeps three horses, two pigs, geese, and goats) buzz around our heads. Animal skulls from past hunting expeditions lie on a dresser, baring their fangs at us and almost staring with their hollow eye sockets. Several elite MMA fighters that comprise Cerrone’s team wander in and out of the house performing various construction tasks for their host. And, of course, Thomas Rhett is blaring on the stereo. But it’s my questions that seem to be distracting Cerrone.

“Who measured this? Jesus!” he exclaims, reacting to a piece of trim he knows full well he measured and cut himself but mysteriously does not fit the window. He could easily blame me for taking his mind off the project (please don’t knock me out, Donald), but he just shakes his head and goes back to the living room and its rotary saw to cut the plank again. “We do it nice because we do it twice,” he says. “That’s the motto around here.”

As an undersized kid (Cerrone claims he was little more than 100 pounds throughout high school), he felt the need to prove himself regularly—usually with his fists. He was diagnosed with ADD, and when Cerrone’s rebelliousness became more than his parents could tolerate, they sent him to live with his paternal grandparents in Denver at age 14. Cerrone doesn’t blame them. “I was the worst kid ever,” he says.

With his grandparents, however, Cerrone received unconditional love. “Whatever I wanted to be or do my grandparents would support me 100%. I got into magic as a kid and they bought me all the expensive tricks. I wanted to go four-wheeling, so my grandpa built me a machine.” When he got interested in bull riding they attended every rodeo, and when he had his first pro kickboxing match they flew to New York City to see him compete (he won).

“They never really cared about me fucking up. Whenever I got in trouble my grandmother would always say, ‘You know what you did.’” Acknowledging his own mistakes had the effect of making Cerrone feel more accountable, and he believes it helped save him from himself. “I could never lie,” he says.

When You Make a Promise, Keep it

In between answers Cerrone has been finishing the windowsill. His jiu-jitsu coach is on his patio staining the wood Cerrone cuts with Minwax and it’s coming together nicely. I shouldn’t be surprised. Cerrone has built almost every structure on his property himself since he bought it in 2008, with some help here and there from fighters he’s mentored along the way. He installed the electrical lines and plumbing too, but he downplays the accomplishment.

“It’s all from being a fuck up,” he says. “When you can’t hold one job, you learn a lot of jobs. You learn how to plumb. You learn roofing.” Cerrone still relied on construction work well into his tenure at the WEC—the smaller organization that the UFC used as a farm system for talent in lighter weight classes, until the two merged in 2010. These skills are just a few of many abilities he hopes to foster in the up and coming fighters he welcomes out to the ranch twice per year.

“I loved street fighting because I didn’t have to think about it beforehand. You’d be at a bar, see somebody, and be like, ‘What’s up, motherfucker?’ and just fight. This next fight I have [with Matt Brown], I have to think about him every day. It’s the fear of letting everyone down. That’s the hardest part of the sport.”

For $1000, green MMA pros can ascend the nearly 8,000 feet above sea level to the BMF Ranch (if you know anything about Cerrone, the meaning of the initials should be obvious) and train with Cowboy. They also get access to the nearby Jackson-Wink MMA Academy, which originally drew Cerrone to New Mexico and remains his primary fight camp. When they’re not learning the fight game, the men will learn the trades that kept Cerrone going until his UFC career took off. They live in a two-level 54’x24’ dorm—food is included—and can pick Cerrone’s brain on everything from fight strategy to how to obtain sponsorship and good management; “I tell them what to do and what not to do,” says Cerrone, whose Octagon success has allowed him to invest what he estimates to be upwards of $400,000 in the ranch over the past eight years. Guests usually stay for a month, and past visitors have included welterweight Jonavin Webb and rising UFC lightweight Paul Felder.

Cerrone started the ranch as a business, but his generosity to struggling fighters makes it impossible to turn a profit. He says he doesn’t make any money on his coaching. Fortunately, he does on his pigs. “I can get $400 for that one,” he says pointing to an obese hog that waddles past the window. Assuming he doesn’t eat it himself first.

Do What Has To Be Done

Cerrone has finished the windowsill and even hung some curtains over it. With his domestic duties complete for the day, he’s ready to do some training. Erik “Esik” Melland, Onnit’s master steel mace coach, is staying at the ranch tonight. He introduced Cerrone to the steel mace a few months ago—a thick bar with a solid round ball on one end, akin to something you’d imagine one of Cerrone’s ancient ancestors using to cave in a skull during a village raid. The fighter took to it right away, and Esik is going to lead Cerrone and his buddies through a mace workout that he can then incorporate into his strength and conditioning going forward.

The fighters gather in Cerrone’s gym, a separate building across from the house that includes a regulation-sized Octagon. “Mama Tried,” by Merle Haggard, plays on the stereo. Each grabs a mace as they assemble on the mat in a circle to turn their attention to Esik in the center, who shows them how to swing it. The movements are effective for opening the shoulders and improving range of motion, and the off-set nature of the load—the ball is on one side only—forces maximal core tension to prevent loss of balance.

“It builds grip strength and rotational power,” says Esik, “which translates to striking, wrestling, and jiu-jitsu.” Just holding onto the mace so the momentum doesn’t cause it to fly out of your hands and kill someone nearby provides a grip workout. “It’s primal,” adds Esik. “It builds confidence in what your body can do.”

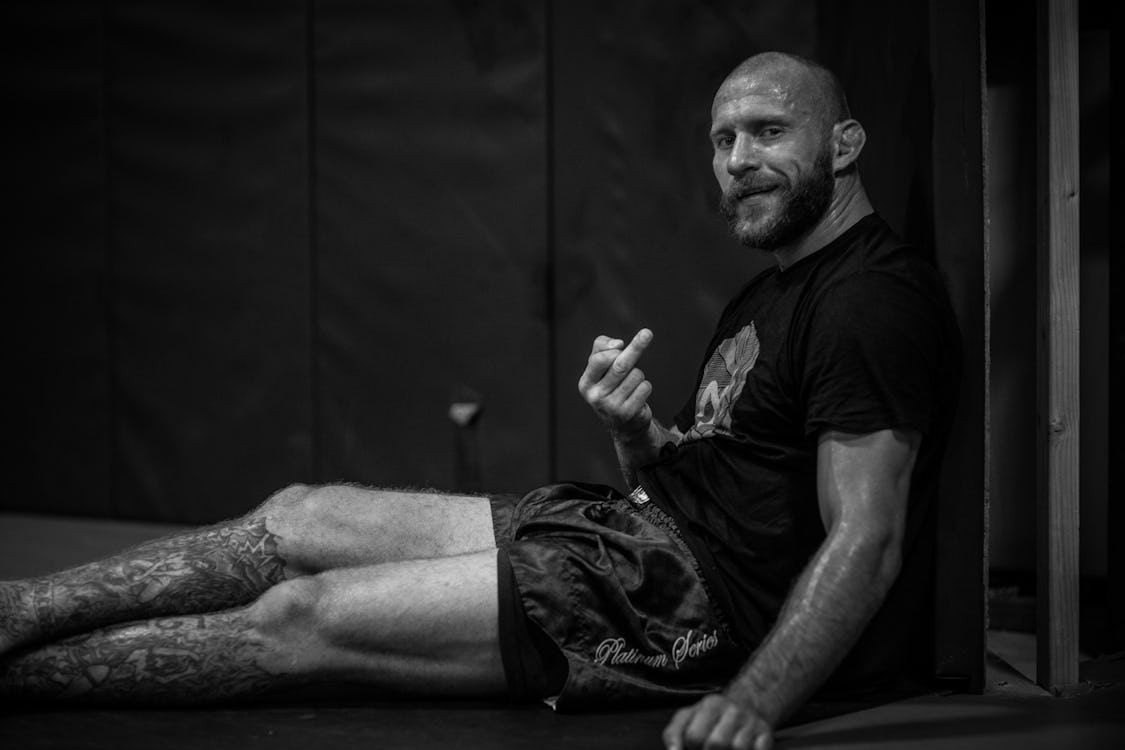

After about a minute of mace work, Cerrone pretends he is ready to tap. “Anybody need a break?,” he asks his men. “It’s hard isn’t it?” Admittedly, it is, but it feels as if the levity is a way to pull himself out of the fire, which makes me think of one of the harshest criticisms fans and pundits alike have leveled against him: he doesn’t take fighting seriously enough.

“We’re coming into turkey season right now, and then it’s pheasant and duck. If someone called me tomorrow and said let’s go hunt this weekend, I’d be fuckin’ out of here.”

“I’m the biggest pussy in the fuckin’ world,” Cerrone says, again being self-effacing and vulnerable. It’s not what you expect from a man who buzz-sawed through 11 of his past 12 opponents as easily as he did the lumber he used to build his windowsill. Is Cerrone—deep down—hungry enough to win the world title we all know he possesses the raw talent to? Or does he lose focus, give in to temptation, and let opportunities go by?

Much has been written about Cerrone’s wild life outside the cage. He says that he hasn’t gotten on a bull in two years since UFC president Dana White forbade him to, but he still wakeboards, hunts, sky dives, and enjoys a drink or two (as well as fruit rollups) whenever the mood strikes him—even on days leading up to a fight.

I ask him if he can live up to his potential dividing his time like that, and taking potentially career-ending risks.

“I don’t know,” he says, turning his head away. “I guess that remains to be seen.” And while I hear a twinge of doubt in his voice, I don’t hear regret. “We’re coming into turkey season right now, and then it’s pheasant and duck. If someone called me tomorrow and said let’s go hunt this weekend, I’d be fuckin’ out of here.”

It’s talk like that that has led to White making comments that Cerrone is “inconsistent,” failing to win the big fights when his career is most in need of them, such as his lightweight title shot against Rafael Dos Anjos (Cerrone lost by TKO) and against perennial contender Nate Diaz (a performance that nonetheless earned “Fight of the Night” honors).

Cerrone doesn’t disagree, but counters that life is about more than fighting, and so is he. “I’m sure if I dedicated my life solely to it I’d be great, but I’m young and there’s too much life to be lived. Being the greatest in the world sounds good but it takes more than people think, and maybe it’s not that fulfilling.” But maybe it is.

Remember That Some Things Aren’t For Sale

According to Hector Munoz, Cerrone’s jiu-jitsu coach and training partner since 2007, Cowboy’s problem isn’t that he needs to buckle down—rather, he has to lighten up. “What he needs to work on most is just believing in himself. He’s already figured out the formula.”

With 10 years of pro MMA experience under his belt, Cerrone has the technique and mindset he needs to win, and he’s never lost a fight due to poor conditioning, or—God forbid—quitting on himself. None of his coaches or training partners have ever reported him showing up to workouts hungover, or even late. And since Cerrone’s move from the 155-pound division to 170, which is closer to his natural walk-around weight of 175–180, Munoz says he’s happier than ever, and happiness is the key to victory.

“The diet messes with your head. It makes you not yourself. Now that he doesn’t have to cut weight, he’s happy. And when Cowboy’s happy, we call that ‘styling’. He’s styling out there, walking around with confidence. When he believes he’s the best in the world there’s nobody who can touch him.”

“You meet a lot of these fighters and most of them aren’t very intelligent. Donald is. If he doesn’t know how to do something, he’ll learn. And he learns to the extreme.”

Munoz also argues that Cerrone’s extra-curriculars aren’t so much a distraction but a necessary part of a work-life balance that keeps him enjoying the sport. And just because he’s out on some adventure in the morning doesn’t mean he won’t be back to bust his ass in the gym at night. “Some days we’ll get up, do a swim workout, then go for a three-hour Harley Davidson bike ride to the lake. Rip through the lake all day, then ride the bikes three hours back home and have a monster MMA workout. A lot of people wouldn’t want to train at that point, but he does.”

Onnit’s founder, Aubrey Marcus, who has been working closely with Cerrone since his meteoric rebirth at welterweight, sees a parallel to Olympic gold medalist Bode Miller. Famous for indulging in late nights before ski races, and pickup basketball games before world championships, Miller has had similar accusations of reckless behavior made against him despite having medaled at three different Olympic Games. “What people don’t realize is that at the level of Bode or Cowboy, the performance is 95% mental,” says Marcus. “If something outside of the sport offers a 10% mental boost and a five percent physical detraction, it’s still the right thing to do. Donald does what he has to in order to get his head right. It’s when those guys stop having fun that there is a problem.”

Live Each Day With Courage

Like many fighters, Cerrone’s ability to face up to danger gives him both a tremendous competitive edge and a penchant for self-destruction. In 2006, he was racing motorcross and missed a jump. “I stood up and my guts fell into my hands,” he says, and, picking up his shirt to show me the scar, I can tell he’s not exaggerating.

Doctors told him he’d never fight again, and that one body shot could rupture his spleen and he might bleed out without even knowing it. Of course, Cerrone ignored the advice and was fighting again—still with two broken ribs—a few months later.

He’s just as reckless with his mouth. When he called UFC light-heavyweight champion Daniel Cormier a “faggot” for his careful handling of Anderson Silva at UFC 200, one of his main sponsors threatened to drop him. “I don’t mean it like a homosexual,” he says. “I mean it like ‘you’re being a faggot!’ It’s just a word I had a habit of using. I meant Cormier was being a bitch. But I’m not homophobic, and I didn’t mean to offend anyone. You can suck any dick you want—it makes no difference to me.”

Brash, yes. But fearless? No. Cerrone freely admits that he’s “deathly scared” before a fight, but not from the threat of pain, injury, or humiliation. He’s a victim of his own imagination. “I loved street fighting because I didn’t have to think about it beforehand. You’d be at a bar, see somebody, and be like, ‘What’s up, motherfucker?’ and just fight. This next fight I have [with Matt Brown], I have to think about him every day. It’s the fear of letting everyone down. That’s the hardest part of the sport.”

At age 33, it’s unclear how many wars Cerrone has left in him. If he beats Brown, he’ll almost surely fight for the welterweight title next year. A greater concern, perhaps, is his health. Cerrone estimates the number of concussions he’s suffered at “a million,” not just from blows received in the Octagon but accidents in his other activities. As a result, he rarely spars anymore, preferring pad work and drilling instead. “I’ll probably be a slobbering idiot one day,” he says. All the wear and tear led Cerrone to meet with Onnit founder Aubrey Marcus, and ultimately to try a range of supplements that he swears have helped.

“The diet messes with your head. It makes you not yourself. Now that he doesn’t have to cut weight, he’s happy. And when Cowboy’s happy, we call that ‘styling’. He’s styling out there, walking around with confidence. When he believes he’s the best in the world there’s nobody who can touch him.”

“I always thought supplements were bullshit,” he says. “But I tried them for 20 days and damn, man, I honestly feel the difference. I wake up not as sore. I have more drive to train. When I take the Total Strength and Performance and the Shroomtech, it gives me energy without Red Bull or candy.” Experimenting with Alpha BRAIN® and New MOOD® have helped too. “My mood is more consistent. I’m more focused. I feel fucking good.”

If, however, Cerrone’s future is as grim as he fears, it seems he’s chosen the best possible partner to help him navigate it. Lindsay Sheffield has been his girlfriend for the past six years, and the two live together on the ranch. An ICU nurse now studying to become a doctor, Cerrone jokes that if he ultimately has medical problems, “she’ll take care of it.”

“We met at a bar in Texas,” Sheffield says. “My friend and I were playing pool, and the winner got to pick somebody for the loser to dance with. I lost and my friend picked Donald.”

Every bit the adrenaline-junkie Cerrone is, Sheffield says the pair do everything together, from renovations on the house to workouts with the team. If he should ever tire of the fight game or be forced to leave it, Sheffield says Cerrone has more options than he’d ever give himself credit for.

“You meet a lot of these fighters and most of them aren’t very intelligent. Donald is. If he doesn’t know how to do something, he’ll learn. And he learns to the extreme.”

I ask Cerrone how he’d like to be remembered outside of fighting and he stares me down with blue eyes that remind me of a gas burner on low. “Just as a wild motherfucker who was down for anything, always.” Then he softens a bit. “Someone you can count on. I always do what I say I’m going to do and I’m always on time. It’s all in the cowboy code I’ve got hanging in my kitchen.”

Cerrone faces Matt Brown at UFC 206 on Saturday, Dec. 10, only on pay-per-view.

)