Welcome to the great free-weight debate—the ongoing argument over which classic and widely used training tool is best, the barbell or dumbbell. For hundreds of years, people have been trying to pick the winner by analyzing every possible feature and benefit of each tool, respectively. Which is more functional? Which should you use in your training? And when would you choose one over the other?

The truth is, there are no one-word answers here. Both the barbell and dumbbell are amazing implements that can bring value to your training, and you should use both, if possible. But to provide the ultimate guidance, we’ve enlisted the help of some reputable fitness experts to break down when, why, and how to use barbells and dumbbells to reach your goals.

“The key with training is to not get married to only one method or one training tool,” says Zach Even-Esh, founder of the Underground Strength Gym in Manasquan and Scotch Plains, NJ (zacheven-esh.com). “It would be closed-minded to do so, and in turn would hinder your results. My preference is to mix barbell and dumbbell work, and find the right time and place for each.”

The History of Barbells and Dumbbells

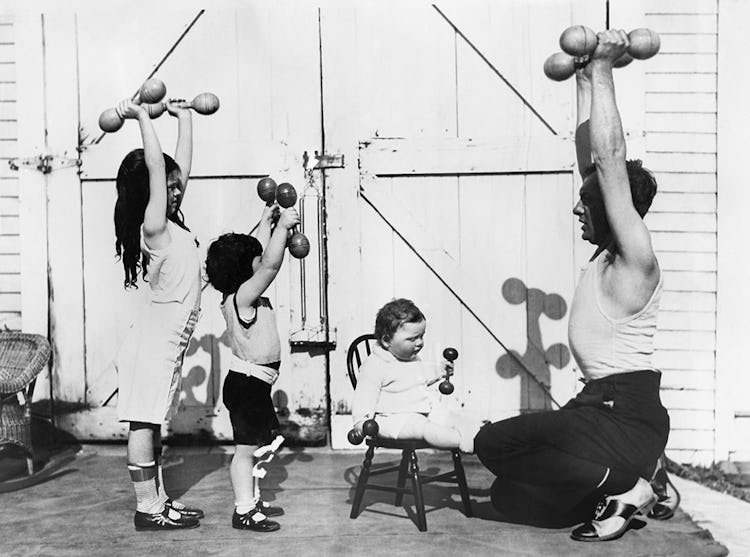

Although historical records are limited, dumbbells seem to have first appeared in a rudimentary form in ancient Greece, as early 700 BC. Halteres, as they were called then, were small stone implements used by long jumpers. Athletes would swing the weights backward, and then forward before takeoff, to create greater momentum and thrust for the jump.

Now fast-forward more than two thousand years. In the 1700s, church bells began being used for exercise. To silence them, the clappers were removed, and so the name “dumb” bell was born. By the early 1800s, the dumbbell better resembled the form we know now (handle in the middle, equal weight on both ends), and was being used in European schools and exercise classes, as well as in the military. (Interestingly, “Indian clubs,” the forerunner to steel clubs, were just as popular, if not more, at the time in Europe and Asia.) By the end of the 19th century, gyms in both Europe and America were equipped with dumbbells.

Barbells actually became popular after dumbbells did, reportedly in the mid-1800s. But they caught on quickly. The vintage “globe” barbell came first (the weights on the ends looked like planets), followed by the plate-loaded barbell. In 1896, weightlifting officially became an Olympic sport, with both dumbbells and barbells used in competition. Then, in 1928, a German named Kasper Berg introduced the revolving-sleeve barbell, which was more or less the modern Olympic bar we know today.

Through the rest of the 20th century, dumbbells and barbells continued to evolve as technology and sport science advanced, strength and physique competitions became more and more popular, and the public’s interest in health and fitness exploded. Today, dumbbells and barbells are as popular, and effective, as ever, and come in various forms to accommodate individuals of all levels.

The Different Types of Dumbbells

There are two basic types of dumbbells: fixed-weight dumbbells and adjustable dumbbells.

Fixed-weight dumbbells are the kind you see in commercial gyms, usually ranging (in pairs) from five-pound weights up to 100+ pounds, and typically in five-pound increments. The weights are fixed to the bar, and cannot be adjusted.

Adjustable dumbbells allow you to change load quickly, by sliding weight plates on and off the handle and clamping it, or by pulling a pin or turning a dial that locks and releases the plates. They, too, typically range from five to 100+ pounds, in increments of five pounds. Adjustable dumbbells tend to be a little more rickety than the fixed-weight kind (you better make sure the weight is secured, or it can fall off the handle during use), and can be a bit awkward to use (heavy weight often means lots of plates that make for a long dumbbell that can be hard to move around your body), but they’re cost-effective, space-efficient, and a solid choice for a home gym. (A full set of fixed-weight dumbbells is expensive and takes up a lot of room.)

The Different Types of Barbells

Like dumbbells, barbells can be fixed-weight or load-adjustable, though the latter is the more common type.

The standard plate-loaded Olympic barbell, the kind you see at any serious gym, weighs 45 pounds on its own and is approximately seven feet long. The middle part of the bar has knurling (rough grooves) to optimize traction, while the outer rotating “sleeves” (where you load the weight) are smooth and thicker, to fit standard Olympic weight plates.

Similar style plate-loaded bars also come in smaller sizes (25 pounds, and shorter), but these are less common than standard Olympic bars.

Fixed-weight barbells are typically found at large commercial gyms, and are stored on dedicated racks. They may range from 20–100+ pounds, and often in 10-pound increments. These barbells are considerably shorter than Olympic bars, and are designed for convenience on lighter-load exercises, as well as for beginners.

All of the barbells described above are straight bars. Other types of barbells offer different designs, including curves in them that help the lifter perform an exercise more efficiently or safely. The EZ-bar (typically used for arm exercises) and trap bar (for deadlifts) are two examples.

Differences Between Barbell and Dumbbell Exercises

Most of the time, when you use a barbell, you’ll hold it with both hands. As we’ll discuss in the next section, this allows you to stabilize the weight you’re lifting to a great degree, and that makes it easier to lift heavy, providing maximum overload to your muscles. Training with a barbell is most applicable to weightlifting sports (Olympic weightlifting, powerlifting, CrossFit, for example), where the barbell is used in competition. In contrast, when you use dumbbells, each hand moves independently. You have the option of lifting either one or two dumbbells at a time, but because your hands aren’t fixed to one bar, the range of motion on any lift is going to be greater, and so is the challenge in stabilizing it.

When doing one-arm dumbbell exercises (e.g., one-arm dumbbell rows, one-arm dumbbell concentration curls, etc.), where the non-working side is not holding a dumbbell, you’re training “unilaterally” (one side at a time). Unilateral training is great for targeting a weak side, and increasing the range of motion for a muscle group. It also works your body in a way that’s more in line with how you move it in real life. Often times we need to use one side of our body while stabilizing the other side (running, throwing, punching, etc.), so dumbbell exercises are highly functional.

Benefits of Using a Barbell

Having your hands locked into a fixed position via a barbell offers one major benefit that you really can’t duplicate to the same degree with any other workout tool: strength. Specifically, high-end maximal strength—the ability to produce as much force as possible.

Barbell lifts, where both legs/arms are working in unison (such as in a back squat, bench press, and deadlift), allow for maximal loading. This is why world-record lifts are recorded with barbell exercises (no one cares how much you can DUMBBELL bench press). However, such gains in overall strength require sacrifice in other areas. A lifter with a 300-pound one-rep max (1RM) on bench press probably won’t be able to press a pair of 150-pound dumbbells, because stabilizing the two weights is too difficult.

“A more stable load means you can add more weight and control it a bit more with larger muscles,” says John Rusin, PT, DPT, CSCS, owner of the online fitness platform John Rusin Fitness Systems (DrJohnRusin.com). In other words, when you use a barbell, you won’t be calling upon smaller (and weaker) stabilizing muscles to the extent you do with dumbbells. With barbell exercises, the strongest, most powerful muscles are taking the brunt of the load. (More on stabilizing muscles in Do Barbells and Dumbbells Use Different Muscles? below.)

It’s pretty clear, then, that the barbell is a critical tool for anyone looking to truly maximize muscular strength—including competitive lifters, athletes in strength-speed sports like football, basketball, and track and field, and any gym enthusiast with lofty 1-rep max (1RM) goals. Because the barbell accommodates heavy loading, and big weights recruit a greater number of muscle fibers, one can also argue that barbell training is crucial for maximizing gains in muscle size. You’d be hard-pressed to find a bodybuilder or other physique athlete who has never made at least some use of it.

Benefits of Using Dumbbells

Whether you’re using one or two at a time, dumbbells allow for both greater range of motion (ROM) and more freedom of movement than an equivalent barbell exercise. Let’s use the barbell and dumbbell variations of the bench press to illustrate these points.

With a barbell, your ROM is limited to the point at which the bar is touching your chest at the bottom of the lift. With dumbbells, you’re able to bring your hands lower at the bottom simply because there’s no bar stopping you at chest level. The obvious benefit of greater ROM is increased joint mobility. “Many individuals and athletes have limited mobility in joints like the shoulders, elbows, and wrists, so dumbbells can offer a more movement-friendly motion and help restore that mobility,” says Even-Esh.

As for freedom of movement, your hands are in a fixed position when using a barbell; you’re not able to rotate your wrists or change the orientation of your hands in any way during a set. Dumbbells, however, allow you to freely move your hands independently and rotate your wrists at any point during the movement. This is a key benefit if you have injuries that act up when you lift with a barbell. You may find that, because dumbbells allow your arms and legs to find their own best paths, you don’t experience the same joint pain you get from barbell lifts. So injury-prevention, rehabilitation, and all-around more joint-friendly strength training are all more possible with dumbbell work than with barbell.

ROM and freedom of movement can also be huge for helping you build more muscle, as compared to barbell exercises.

“You can look at this as a sliding scale,” says Rusin. “Bodyweight training is the highest form of rotational requisite, where we can truly explore space. And then on the opposite side of the spectrum is machine training, where you literally lock yourself into position, have little to no freedom of movement, and you move a weight from point A to point B on a strict range of motion through a specific pattern. A barbell is closer on the scale to a machine, and dumbbell movements are closer to bodyweight exercises. Both pieces of equipment are very advantageous, but if the goal is to build muscle, especially working in that 8–12-rep hypertrophy range, dumbbell exercises are preferable.”

Another key benefit of using dumbbells is muscular balance from side to side (left to right). When doing a barbell exercise, your dominant arm can compensate for the weaker arm. This may help you get the weight up, but it will only exacerbate any imbalances you have, and could eventually lead to injury. With dumbbells, each side carries its own weight, so the stronger arm can’t make up for the weaker one. This comes into play even when doing bilateral dumbbell exercises (both arms lifting the weights at that same time), though unilateral exercises can be used to further isolate each side, particularly the weaker one.

Dumbbell training is a great way to identify a lagging side, and immediately begin to correct it. “Using dumbbells develops unilateral strength, which can help bring up your weaker side [usually your non-dominant side],” says Bill Shiffler, owner of CrossFit Renaissance in Philadelphia, and a competitive amateur bodybuilder (crossfitrenaissance.com). “This will be beneficial overall, and also translate into you being able to move more weight on a similar movement when you load up a barbell. For example, dumbbell bench presses can make your barbell bench press stronger.”

Dumbbells also accommodate countless isolation (single-joint) movements, like chest flyes, lateral raises for the delts, and triceps kickbacks. These moves can’t be done with a barbell, so if maximum muscle growth is your goal, you can’t train exclusively with a bar. These exercises often get bashed for not being “functional,” but even non physique-focused lifters should make some use of them. They’re highly effective for targeting specific muscles, and can play a role in overall performance and injury-resistance.

“There’s huge value and ROI to performing isolation movements, regardless of what your goals are,” says Shiffler. “Dumbbells can hit muscles in a way you simply can’t with barbells.”

Are Dumbbells Safer Than Barbells?

Dumbbells don’t allow you to use the same kind of crushing weight that barbells do, and they’re (arguably) less awkward to use. They also mostly lend themselves to less risky exercises. Both Even-Esh and Shiffler, for example, generally consider the one-arm dumbbell snatch a safer variation than the more complex Olympic barbell snatch. But that doesn’t mean dumbbell exercises are injury-proof. With improper form, you can hurt yourself just as easily on a dumbbell press, curl, or triceps extension as you can with the barbell version. “Thinking that dumbbells are an inherently safer implement to use in your program can be a mistake,” says Shiffler.

For instance, it’s not uncommon to pull or tear a pec by pushing the range of motion on dumbbell chest presses or flyes too far. And simply setting up for those exercises—rocking back onto the bench to get into position, or rocking back to a seated position at the end of a set—can be tricky.

With that said, the barbell needs to be treated with more respect, generally speaking. “Any athlete and individual must earn the right to train with a barbell,” says Even-Esh. “Exercises like the squat, deadlift, military press, bench press, snatch, and clean require a solid baseline of strength and skill in moving properly. Before an individual can perform basic barbell lifts, I want to see a foundation of strength built through calisthenics, resistance-band work, sled work, dumbbells, and kettlebells.”

The barbell is simply a more unforgiving implement. With no room to adjust your hand/arm position during a set, the path of your range of motion is very limited. If your shoulders, knees, or lower back aren’t agreeable to it, you can get hurt. This is why there are far more back injuries from back squats and deadlifts than there are from the dumbbell versions of those lifts.

“I suggest staying clear of a barbell if you’re someone who already has a great deal of injuries, or if you have noticeable muscle imbalances, as a barbell can tend to make the imbalances more prominent,” says Jim Ryno, owner of Iron House, a home-gym design and remodeling company in Alpine, New Jersey (Iron-House.co). “I tend to lean toward barbell use for clients that are primarily looking for serious strength gains and want to engage in performing 1RM attempts.”

Do Barbells and Dumbbells Use Different Muscles?

In any exercise you do, you’ll hit the same target muscles whether you’re using a barbell or dumbbells. For example, both a barbell back squat and a dumbbell goblet squat are primarily hitting the quads, with some activation of the glutes and hamstrings as well. A barbell curl and a dumbbell curl both work the biceps. The degree of activation will vary, however, according to how your body moves, and, as already explained, you do move differently using dumbbells versus a barbell.

For instance, in the dumbbell goblet squat example, form dictates that your torso will be more upright than it would be doing a back squat. For many people, that involves the quad muscles to a greater degree, and de-emphasizes the glutes and hamstrings. When you curl dumbbells, you have the option to supinate (twist) your wrists outward as you bring the weight up, which you can’t do curling a straight bar. That can give you greater activation of the biceps and forearm muscles.

Apart from different movement paths and ranges of motion, dumbbell exercises differ from barbell moves in one major way: they utilize more “stabilizer” muscles than barbell variations, due to the greater ROM and freedom of movement involved. When coaches and trainers talk about stabilizers, they’re usually referring to relatively small muscles—the rear delts, rotator cuff, serratus anterior, and levator scapula in the upper body, or gluteus minimis and piriformis in the hip region.

Generally speaking, the less you have to rely on stabilizers for an exercise, the more weight you’ll be able to move, since stabilizers are smaller and weaker than prime movers like the pecs, lats, quads, and glutes. As the saying goes, you’re only as strong as your weakest link; thus, your stabilizers are the limiting factor when doing a given movement with dumbbells versus a barbell.

It can be said, then, that dumbbell exercises activate more muscles (big ones and small ones combined), while barbell exercises get the most out of the larger muscles. Yet this doesn’t mean the latter is best for gaining size.

“I’m really not a huge believer that the barbell deadlift, squat, and bench press are really best to build muscle, just because of the way they fit on the body,” says Rusin. “These exercises lock you into position, giving you less natural rotation through space [freedom of movement], which is where we tend to get better peak targeting of muscles and a stronger mind-muscle connection. When we lock that rotation, we tend to shift the focus naturally to a strength emphasis pattern, where the goal becomes more global in terms of moving a load from point A to point B.”

As implied, Rusin favors dumbbells over barbells for building muscle, with his rationale focused on movement quality.

“I tend to not program barbell moves for anything over around 6 repetitions,” he says. “The barbell has the most loading capacity, but the biggest limiting factor for getting into extended rep ranges is a lack of movement quality. People tend to break down at the midsection on big barbell lifts, and the core is the first thing to fatigue and create a weakness, typically after you get past around 6 reps. You can build muscle in any rep scheme, but working in that 8–12 rep range is important because, one, you have enough weight to create mechanical tension, and two, the sets are long enough to keep the muscles under tension for the time it takes to create great metabolic stress in the tissue—another factor for growth. That’s what really creates the so-called perfect stimulus for hypertrophy [muscle gain].”

In other words, to create the perfect storm for muscle gain, do some barbell work for low reps, and dumbbell work for higher reps.

Our Favorite Barbell Exercises

Juan Leija, General Manager of Onnit Academy, and a coach at Onnit Gym in Austin, TX, recommends the following barbell exercises to build overall strength and stability. Practice them for sets of 6 reps or fewer to start, using light weight until you’ve mastered form. Follow Leija on Instagram, @juannit_247.

Deadlift

Many coaches and lifters consider the deadlift to be the best exercise you can do with a barbell, and the best test of total-body strength. It’s particularly good for building strength in the hips, lower-back, and grip.

Step 1. Stand behind the bar with feet between hip and shoulder-width. Draw your shoulder blades together and downward—think, “proud chest.” Now bend your hips back, as if trying to touch your butt to the wall behind you. Your head, spine, and pelvis should form a straight line.

Step 2. Grasp the bar overhand, and take a deep breath into your belly. Make sure your shoulders are pulled back and down again, and brace your core. Begin to push your heels into the floor to lift the bar off the floor. Come up until your hips are locked out and you’re standing tall.

Floor Bridge Press

Pressing from a bridged position involves the lower-body in the lift, making for a more athletic bench press exercise. Glutes are often a weaker muscle group, because most people spend so much time sitting, and don’t train the glutes directly. This exercise helps to bring them up while training upper-body power and strength.

Step 1. Set the bar on a power rack, low to the floor. Lie on your back on the floor and bring your feet in close to your butt. Tuck your pelvis so that it’s in line with your spine, and brace your core. Drive through your heels to lift your butt off the floor (keep your core braced so you don’t hyperextend your lower back).

Step 2. Grasp the bar with hands just outside shoulder width. Pull the bar out of the rack and hold it above your chest. Take a deep breath into your belly, and lower the bar until your triceps touch the floor. Pause a moment, and press the weight back up. Maintain your bridge position the entire time.

Offset Overhead Press

Learning to stabilize an uneven load helps prepare your body for movements in sports and in life, which are often asymmetrical. Keeping the bar straight on an overhead press that’s unevenly loaded will develop stability in the shoulders. Complete your reps on one side, and then switch sides and repeat. (Rest between sides if you feel you need to.)

Step 1. Load only one side of the bar. Beginners (and those new to the movement) should start with only 10–25 pounds. Grasp the bar with hands at shoulder width, and take it out of a power rack, or, clean it up from the floor while keeping your lower back flat. The bar should be just below your chin, and held perfectly straight. Stand with feet shoulder-width apart, and tuck your pelvis under so it’s level with the floor. Take a deep breath into your belly, and brace your core.

Step 2. Press the bar overhead while keeping it as level as possible. Note that you’ll need to lift it slowly to maintain control. Lower the bar back to chin level.

Pendlay Row

Named for the late Olympic weightlifting coach Glenn Pendlay, this rowing variation targets the upper back, lats, and lower back with a strict movement. No bouncing the weight up or using momentum here.

Step 1. Stand behind the bar with feet between hip and shoulder-width. Keeping your head, spine, and hips in a straight line, bend your hips back as if you were trying to touch your butt to the wall behind you (allow your knees to bend as needed). Grasp the bar outside shoulder width and take a deep breath into your belly. Draw your shoulder blades down and together (think, “proud chest”), and extend your spine so it’s long and straight.

Step 2. Explosively row the bar from the floor to your upper abs. Lower it back down and let it come to a dead stop on the floor before you begin the next rep.

Suitcase Deadlift

Similar to the offset overhead press, the suitcase deadlift challenges your body with asymmetrical loading in a movement you’re probably not used to doing unilaterally. It’s also killer for the core and grip.

Step 1. Stand to the side of the bar, as if it were a suitcase you were about to pick up. Place your feet between hip and shoulder-width, and bend your hips back to reach down and grasp the bar in the middle. Square your shoulders and hips with the floor, and draw your shoulders back and down as much as you can. Your head, spine, and pelvis should form a long, straight line. Take a deep breath into your belly and brace your core.

Step 2. Drive through your heels to stand up, raising the weight off the floor and to your side. Try to keep the bar as level as possible as you lift it—squeeze it tightly—and avoid bending or twisting your torso to either side. Complete your reps on that side, and then switch sides and repeat.

Landmine Row To Press

Once you’ve gotten familiar with basic lifts like the deadlift, row, and press, combining them into one movement can help you better mimic the demands of life outside the gym. The landmine row to press has you lifting the bar off the floor and overhead explosively, building total-body strength and power—but in a more user-friendly movement that’s also easier on the joints, thanks to the arc of motion provided by the landmine.

Step 1. Load a barbell into a landmine unit, or use the corner of a room. Stand to one side of the bar with feet shoulder-width apart. Draw your shoulder blades together and downward—think, “proud chest.” Bend your hips back, as if trying to touch your butt to the wall behind you. Your head, spine, and pelvis should form a straight line. Grasp the end of the barbell’s sleeve with one arm.

Step 2. Explosively deadlift the bar up while rowing it and twisting away from it. As your free hand comes toward the bar, use it to take the bar from the rowing hand, and allow the momentum to help you follow through and press the bar overhead along the arc that the landmine provides. Start extra light so that you can master the movement in one fluid motion. Complete your reps on one side, and then repeat on the other side.

Our Favorite Dumbbell Exercises

We like the dumbbell exercises below because they offer distinct advantages over their barbell counterparts, including safety, muscle balance, and freedom of movement. All of these exercises can be performed with kettlebells as well, but doing so can be awkward in some cases (due to the kettlebell’s offset handle and ball structure). Kettlebells also provide fewer loading options, as they don’t come in the same weight increments that dumbbells do. The snatch lends itself well to a kettlebell, but you may do better with dumbbells on the other moves until you’ve mastered them.

Dumbbell Snatch

The barbell snatch is possibly the most complex and intricate barbell exercise there is, but its dumbbell counterpart is relatively easy to learn, and offers similar benefits in terms of power. It’s also great for your core.

Step 1. Hold a dumbbell with one hand and stand with feet slightly wider than shoulder-distance apart. Draw your shoulders back and downward (think: “proud chest”). Press your hips back while keeping a long spine—your head, spine, and pelvis should maintain alignment as you hinge at the hips. Bend your knees as needed. Your chest and shoulders should be level with the floor and remain facing forward. Breathe into your belly, and engage your core. Allow your free arm to hang at your side.

Step 2. Powerfully extend your knees, hips, and ankles, drawing the dumbbell straight up and close to your body. The movement should be powered by your lower body, not your shoulders. Your feet may or may not rise off the floor for a moment.

Step 3. Shrug the shoulder that’s holding the weight, driving your elbow up high and backward. The dumbbell should travel in a straight line up in front of you. Think about pulling your whole body under the weight as it rises.

Step 4. When it reaches its highest point (above shoulder level), turn your elbow under the dumbbell. Catch the weight overhead with arm extended as it continues upward.

Single-Arm Dumbbell Row

“This is probably my favorite dumbbell move,” says Rusin. “It targets the upper back and core. You can get your hips involved if you add rotation. It’s killer in terms of metabolic capacity, and will ramp up your heart rate. You can go heavy with low reps, or go lighter with high reps. There are so many different ways you can do it.” The basic one-arm row, in which you get in a stable stance and pull to your hip, is described below.

Step 1. Hold a dumbbell in one hand and stagger your legs. Bend your hips back so that you can rest your free arm on your front knee for support. Your body should form a straight line from your head to your heel.

Step 2. Row the weight to your hip, drawing your shoulder blade down and back. Your upper arm should end up in line with your torso. Complete your reps, and repeat on the opposite side.

Arnold Press

It’s not clear if this movement got its name from Arnold Schwarzenegger, but there’s ample evidence that the Governator—and lots of other famous bodybuilders—used them successfully. Instead of pressing the weight straight overhead, you rotate your wrists and elbows outward. This limits the weight you can use, but it activates more of the lateral head of the deltoid, and can be a good strategy for working the shoulders while lessening the risk of injury. If your shoulders are banged up from years of sports or other activity, performing lighter Arnold presses may be the best way to work them in an overhead pressing motion.

Step 1. Stand with feet shoulder-width apart, and hold the dumbbells at shoulder level with palms facing you.

Step 2. Press the weights overhead, and rotate your wrists outward as you lift, so that your palms face forward at the top of the movement.

Dumbbell Bench Press

No surprise here. You’ve probably done these already, along with everyone else who’s ever gone to a gym wanting to get a pump. But there’s no wonder as to why (nor is there any reason to stop doing them). The dumbbell bench press trains the pecs through a full range of motion, and can be effective for size and strength in any rep range. If chasing a big barbell bench press number has left you with sore shoulders, switching to dumbbells can provide some relief while offering even more stimulus to your pec muscles.

Step 1. Hold a dumbbell in each hand and lie back on a bench. Position the weights at shoulder level.

Step 2. Press the weights over your chest, squeezing your pecs as you come up. Lower your arms with elbows pointing 45 degrees from your sides.

Dumbbell Romanian Deadlift

Strong glutes, hamstrings, and spinal erector muscles are crucial for being able to run fast, jump high, and lift a lot of weight. Any version of the RDL will accomplish that, but the dumbbell variant gives you a bit more range of motion, and the option to alter your technique for the sake of emphasizing one muscle over another. For instance, Rusin says you can hold the weights at the sides of your legs instead of in front to get more glute involvement.

Step 1. Hold a dumbbell in each hand and stand with feet hip-width apart. Twist your feet into the floor to generate tension in your hips.

Step 2. Tilt your tailbone back and bend your hips back as far as you can. Allow your knees to bend as needed while you lower the weights until you feel a stretch in your hamstrings. Keep your spine long and straight throughout. Squeeze your glutes as you come back up to lock out your hips.

)